Overview: Is Hysteria the New Normal?

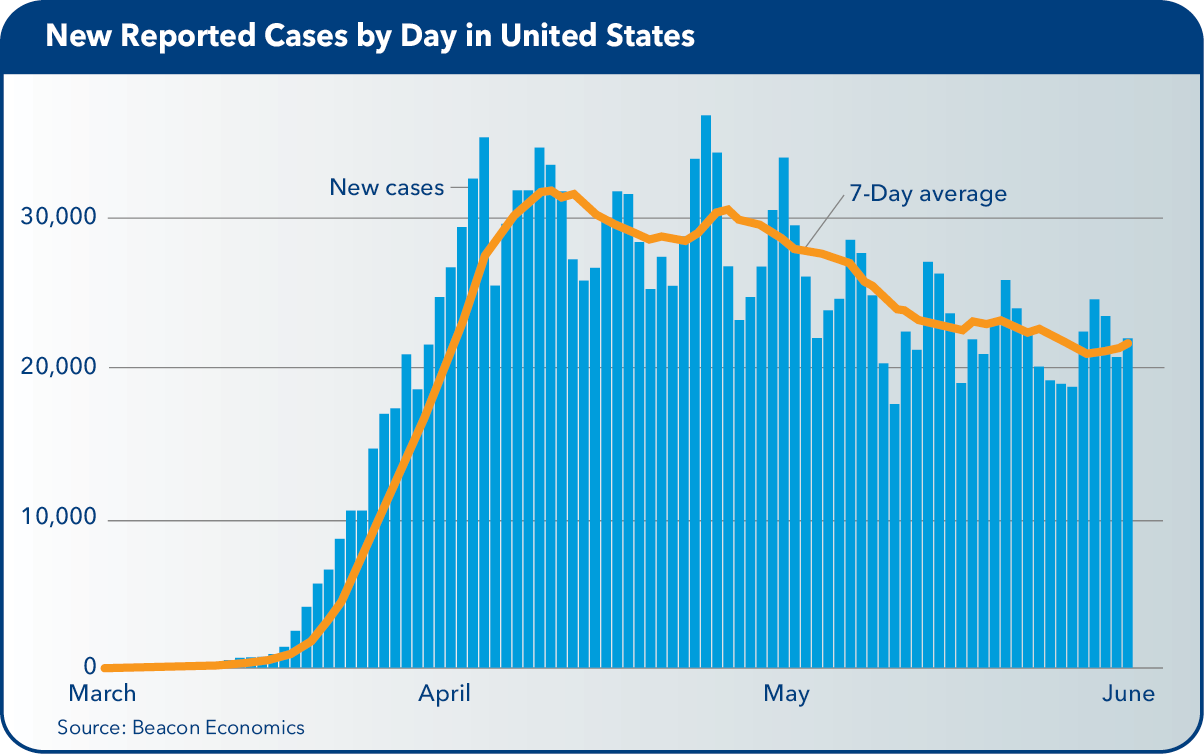

The good news is that the number of new, confirmed cases of the coronavirus in the United States has, at least for now, peaked and appears to be falling. Stay-at-home mandates across the nation have been having their intended effect of limiting the spread of the virus beyond the initial surge.

We are far less cognizant, however, of what the full scope of the economic shock will be, as economic statistics significantly lag public health stats. There is some data for March, but much of the month had passed before public health closures were widely mandated; hence they don’t tell us much. April numbers won’t start arriving until early May.

Guessing Game

Regardless, there is little doubt that these health-mandated closures will cause a record decline in economic activity in the second quarter of the year. How much is a wild guessing game right now as there is no historical precedent for the current crisis and little good data as of yet.

Current estimates from a variety of forecasting organizations suggest second quarter growth could run from -20% to -40%, and we don’t disagree. Those numbers, however, sound far worse than they are as economists have a habit of reporting gross domestic product (GDP) statistics in annualized form. This means that the total output of the economy will contract by -5% to -10% from the first to the second quarter. Still, this is larger than anything experienced in the past.

What Comes Next?

The real debate is over what comes next. As always, the issue has been boiled down to a spelling bee: will it be a “V” recovery or a “U”? Or perhaps a “W,” and for the true pessimist let’s not forget the dreaded “L.”

The broad consensus appears to be “U”— meaning that there will be little bounce following the record second quarter downturn, after which we’ll have a long painful climb back to normality. Under this scenario, unemployment will remain elevated well into 2021 if not beyond. Most of the “U” camp is suggesting a business cycle that is as large or larger than what transpired during the Great Recession.

The problem with these forecasts is that they are leaping to extremely grim conclusions with little basis. While there are many anecdotes and grim news stories—not to mention the universally odd experience of closed schools and empty highways—there is very little hard data yet. And we don’t have any recent economic experiences within the developed world to use as a historical metaphor.

All forecasts right now are, at some level, a leap in the dark. But very few seem to acknowledge this even as they put out extremely negative predictions.

Five Basic Questions

Rather than pretend there is any logical way of building a mathematical model to predict trends in the coming months, in the outlook below, we boil the question of how this business cycle will look into five basic questions that should determine how rapidly the economy can bounce back after what will surely be a record second quarter decline.

Even cursory answers to these questions suggest that while a “U” is certainly possible, it is actually a far less likely outcome. There is little reason to think the economy can’t and won’t, bounce back rapidly—possibly even so rapidly as to call into question whether this entire episode can be accurately described as a recession as opposed to a national natural disaster.

So why have the bulk of outlooks gone so negative? In truth, it is a relatively typical reaction. In January 2019, the stock markets were down 20% and the majority of contributors to the Wall Street Journal’s “Next Recession” consensus survey were predicting a recession within 12 months.

Why? The real estate collapse, rising inflation, rising interest rates, and of course the trade war with China, which was going to do incredible damage to the U.S. manufacturing sector. Of course, none of this came close to occurring. By April, the markets were yet again hitting record high levels.

Obviously, the impacts of today’s public health mandates are substantially more severe than what was happening back then—but the level of hysteria has simply risen proportionately. This kind of reaction is, unfortunately, the new normal.

Not the Great Recession

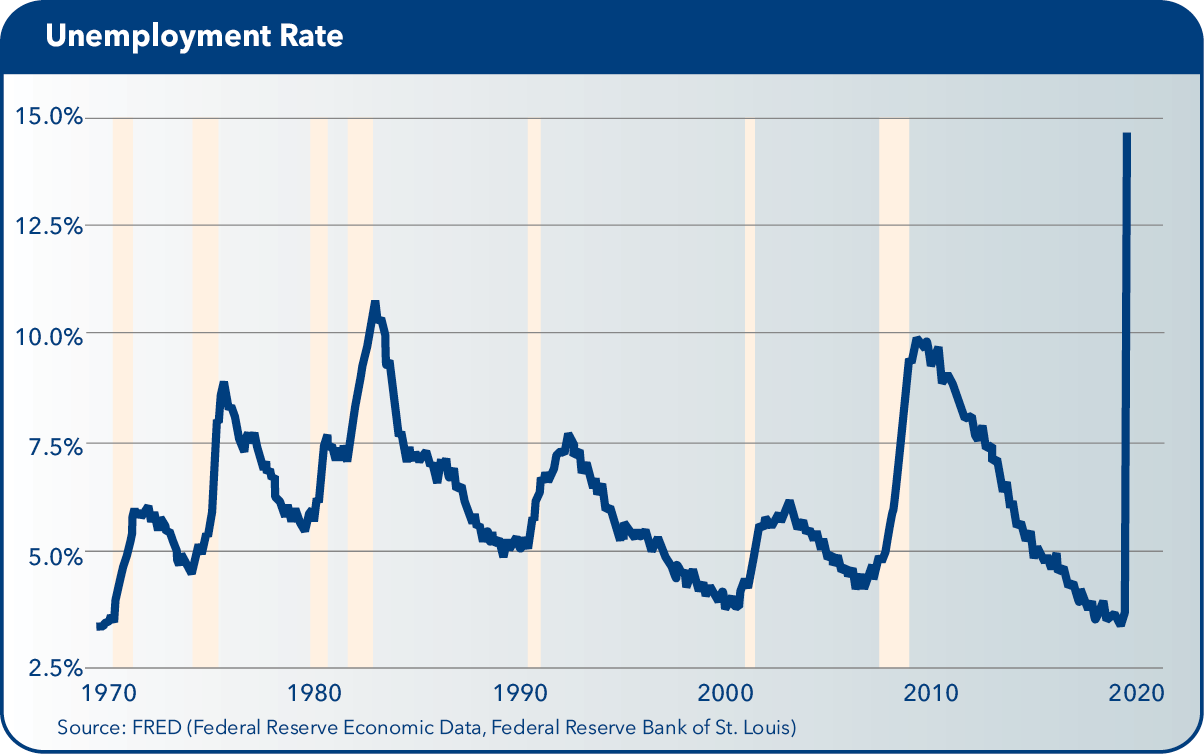

The one data point that really stands out is the 26 million initial claims for unemployment insurance filed over the five weeks since the mandated shutdowns went national. In all of 2008 (the Great Recession) there were 22 million initial claims filed.

Never has the nation had so many people out of work and never has it happened so quickly. Worse yet, historical patterns on unemployment rates are clear: once up they take a long time to fall again. This naturally leads to the conclusion that this downturn will be worse than the last one.

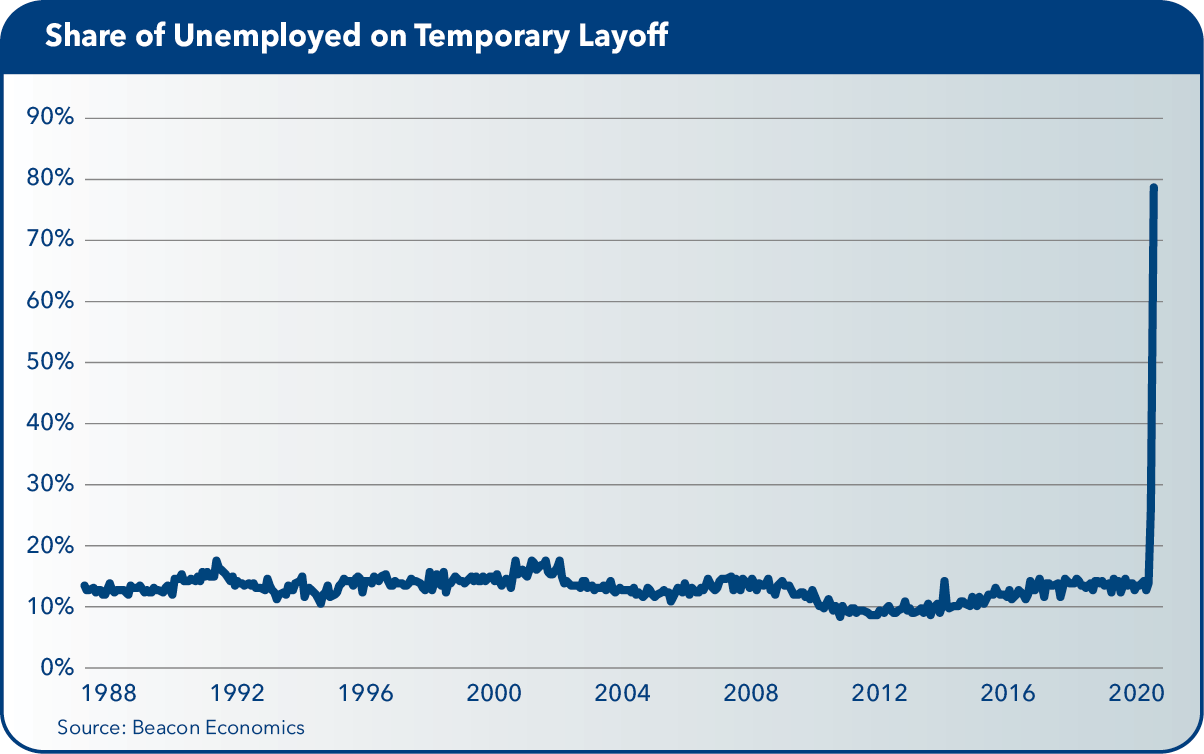

But there is no similarity to what is happening today and what happened in the lead up to the Great Recession, or to any recessions in the last 60 years or more, if ever. This means we can’t necessarily use past patterns as a lens to predict the path ahead.

Collapse of Subprime Credit Bubble

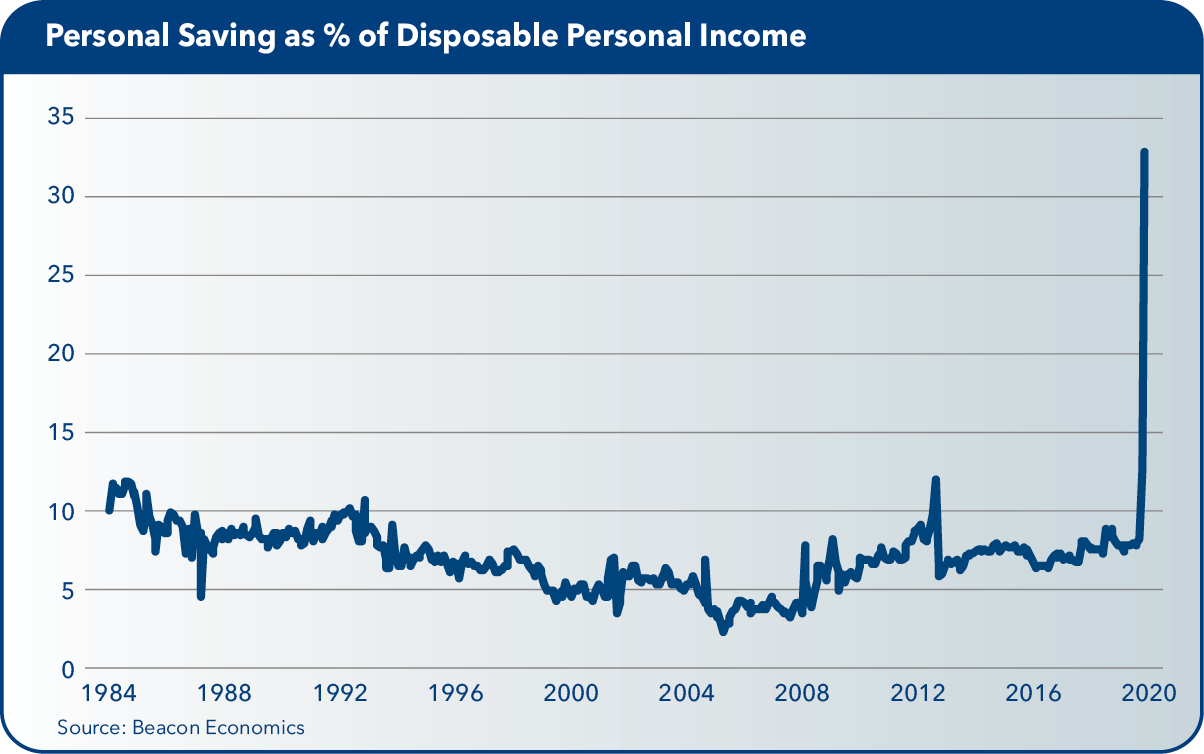

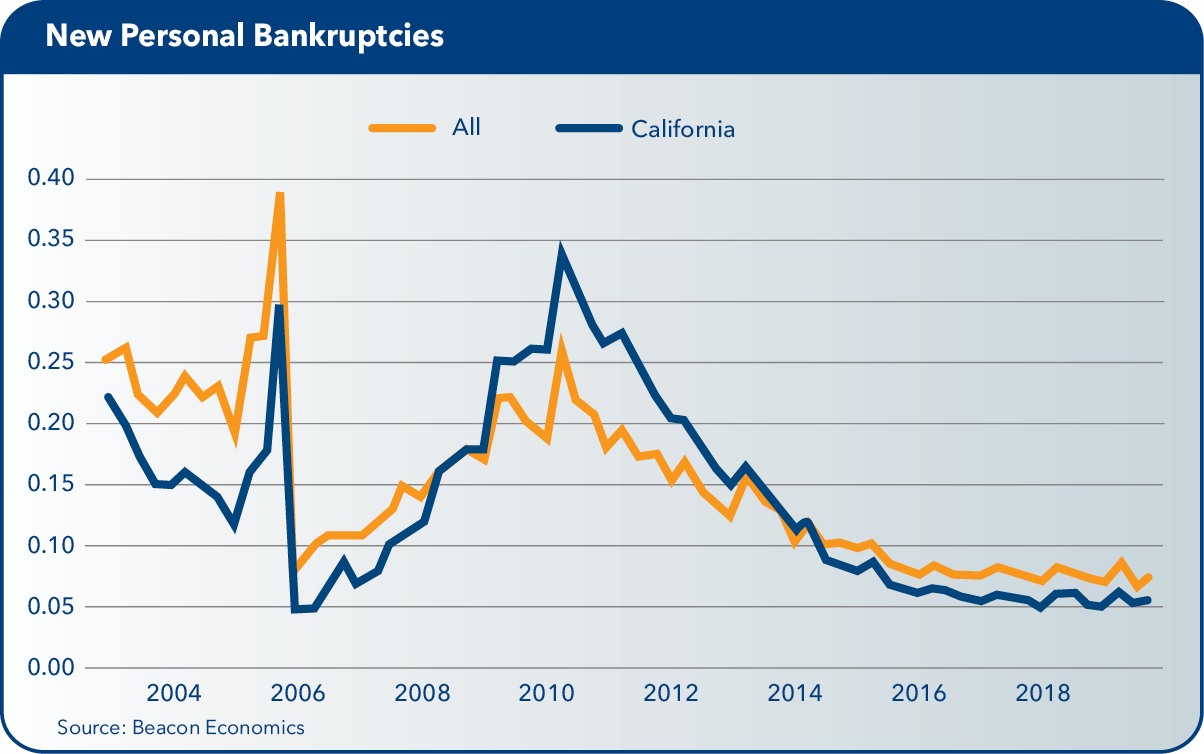

The Great Recession was driven by a collapse of the massive subprime credit bubble, which formed during the preceding years and which pumped $15 trillion in new financial and household debt into the economy. This enormous credit inflow highly overinflated consumer borrowing, and the housing and commercial real estate industries. Easy credit pushed consumer savings rates to the lowest on record while the resulting consumption binge opened the widest trade deficit in decades.

When it finally became clear that the entire subprime lending industry was little more than a giant Ponzi scheme, everything began to unwind. All those businesses that made billions of dollars during the bubble inflation suddenly lost their ability to earn a profit. The crash ultimately caused the permanent loss of millions of jobs connected with the bubble.

Short of another bubble, these businesses/jobs were simply unsustainable. The crisis eventually caused the worst downturn since the Great Depression and the U.S. economy didn’t fully recover until 2015.

What is happening today is nothing like what happened in 2008. The vast majority of people currently applying for unemployment are being laid off from profitable, sustainable businesses that have been shuttered temporarily as a result of public health mandates. If a cure for COVID-19 was discovered tomorrow, these mandates would be relaxed quickly, and there is no reason to think that companies wouldn’t reopen again as viable businesses and bring their employees back to work. What is happening today amounts to temporary layoffs—not permanent job losses.

The difference between now and then is apparent in the data. When a broad negative shock, such as a collapsing subprime bubble, hits the economy, employment in a lagging indicator because businesses shut down and lay off employees only as a last resort. The peak in initial claims for unemployment during the Great Recession occurred in June 2009—the last official month of the recession.

Unemployment Spike Shocks System

This time around the spike in unemployment has occurred first. As opposed to job losses being the result of a shock to the system, in this case, they are themselves the shock to the system. But this shock only lasts as long as the health mandates.

Of course, that should not imply that there are no serious effects. While the world waits for the coronavirus to be contained to the point where it is safe to lift the public health mandates, businesses are losing revenues and families are losing income. This will cause them to fall behind on financial obligations, which can lead to other difficulties such as bankruptcies, defaults, and business failures.

Moreover, the lack of consumer and business spending is sending shock waves through supply chains, leading to additional lost income and revenues, and more strain.

As this continues, true structural damage will begin to build within the economy—harm that in theory could slow an otherwise rapid return to normalcy. How much damage will ultimately determine whether the economic trajectory looks like a sharp V or a protracted U.

Organizing Our Ignorance

“A good forecaster is not smarter than everyone else, he merely has his ignorance better organized.”

—Anonymous

To try and tease out what is likely to transpire in the economy in 2020, there are five basic questions that help approximate how much sustained damage will be generated from the public health-related closures. If the answers suggest a lot of harm—then a slow recovery will be in order. If they don’t suggest sustained harm, then there is no reason to think the economy won’t rapidly return to normal.

When thinking through these questions, we do not necessarily arrive at the conclusion that there will be an extended contraction of the economy.

1. How long until the public health mandates are lifted?

2. How deep is the current shock to the economy?

3. What is government doing in the meantime to soften the blow?

4. How fragile/healthy was the economy when the pandemic first hit?

5. Will there be permanent significant changes in consumer behavior?

Public Health Mandates

As for the first question, the good news is that the number of new coronavirus cases appears to have peaked in the United States as well as in many other hard-hit nations. Some areas are already clamoring to lift certain mandates and even California, which has been very cautious, is beginning to see some partial lifting of controls.

“Hot spots” may reemerge in certain locations, which will slow the process, but remember, we are not the same nation as we were in February when we were given empty assurances from the federal government and were blindly going about our lives with little cognition of the outbreak that was already growing rapidly. This time, the reaction to new outbreaks will be fast and fierce.

The best example is China, which is ahead of the rest of the world in both its post-shutdown surge and its control efforts. If the United States follows roughly the same path, we can expect mandates to start lifting in earnest in late May. Things won’t go back to normal immediately—either in terms of the mandates being universally relaxed or people returning to public life—but the process should begin. Certain activities such as large music festivals and conferences may continue to be prohibited, but smaller scale activities should begin to resume.

Data from China (again) suggest that production should be back up and running in about three months while consumer spending will take about four months to return to normalcy. Either way, mandate wise, expect things to return to normal (mostly) by the third quarter of this year.

Depth of Economic Shock

How deep is the current shock? Many households and businesses are being denied income because of the public health mandates. But those who aren’t losing income are being denied the ability to make desired purchases. This will likely lead to a build-up in demand and financial savings that will give the economy a boost when it reopens. The depth of the current shock will help us understand the balance between the first and second group.

At this point, we don’t know exactly how deep the current shutdown in economic activity is. The obvious issues are with restaurants, hotels, airports, travel operations, and a large portion of retail. But these kinds of businesses don’t make up that large of a share of U.S. GDP. In fact, the closures currently add up to less than 10% of U.S. economic activity in a typical year.

Of course, the shock expands as it works its way into supply chains. This takes time, given the basics of inventory pipelines. There also are productivity impacts as many people are forced to work from home, but again, we have little ability to estimate how big of an impact.

Notably, we are fortunate to live in an era of connectivity where a large share of retail business has and is shifting to an online environment. Many restaurants are offering take out and office meetings are being held over Zoom. All these changes will continue to expand and help mitigate some of the hits the economy is taking.

In total, we anticipate that the U.S. economy will contract by 7.5% to 10% in the second quarter, an annualized rate of 30% to 40%. This is huge historically, but it also suggests the income hits suffered by this 10% of the economy will be offset by pent up demand in the balance of the economy.

Government Intervention

How about the government intervention? There has been an unprecedented degree of public support for businesses and workers who are being negatively impacted. Initial claims for unemployment are up so dramatically in part because the eligibility has been widened to include many workers who would not have been eligible in 2008.

Benefits have been heavily expanded. In California, they can be up to $1,100 per week and there have even been anecdotes about employees who prefer being laid off to working.

Additionally, eligible households are getting $1,200 per person and small businesses are receiving forgivable loans to ensure they keep people employed. Billions of dollars more are going to social programs and direct support for local governments, hospitals, transit, and other services.

The current tally comes $2 trillion-plus in government stimulus, which is enormous. The entire U.S. economy is approximately $22 trillion in size, meaning that on a quarterly basis, overall economic activity runs about $5.5 trillion. As the predicted declines are in the 10% range for the second quarter, that amounts to a half-a-trillion-dollar decline, give or take.

A $2 trillion stimulus package is four times the size of this calculated decline. Much of the stimulus will flow straight into the financial markets, which are currently in full swoon—but the remainder will significantly boost demand.

Pre-Pandemic Economy

How healthy was the economy when the crisis began? There is little doubt that the pandemic is delivering a significant negative shock to the supply chain. Even those industries not directly impacted by the health mandates are being disrupted at some level.

But will otherwise profitable businesses collapse into bankruptcy because of a two-month closure? Will mortgages move into foreclosure due to a couple months of lost income? That all depends on the health of the economy (made up of these businesses and individuals) when the pandemic started.

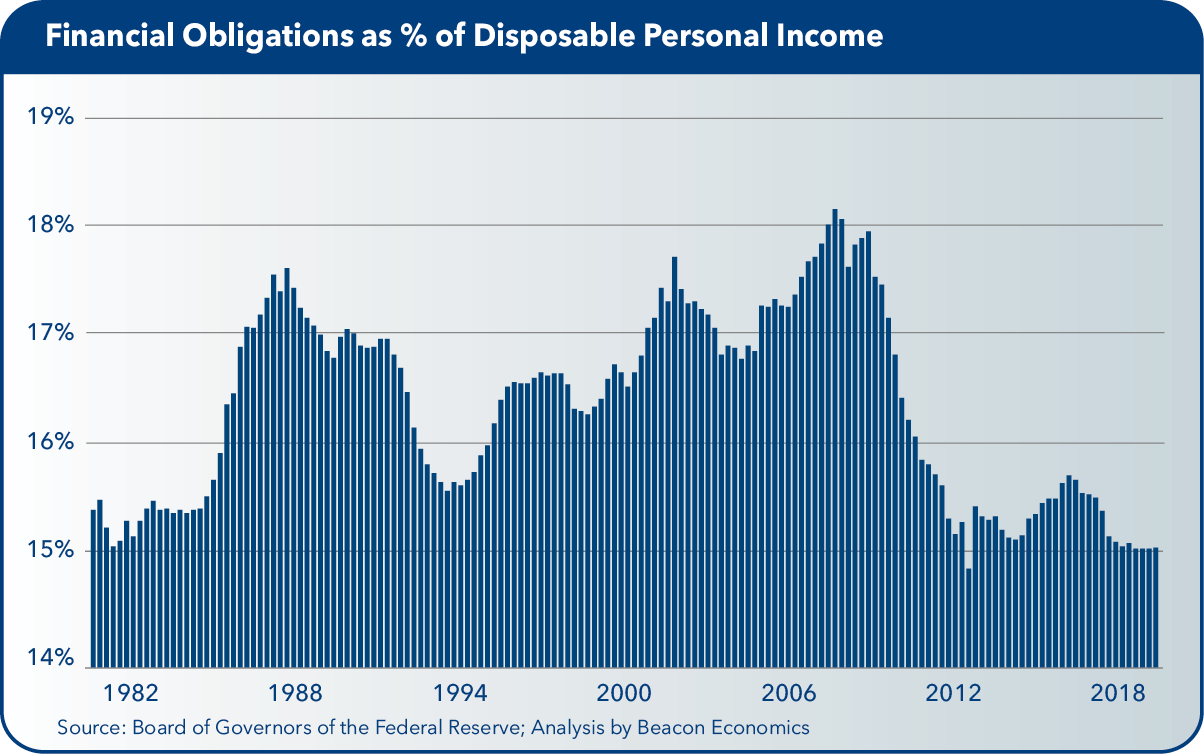

The positive news is that the economy is much less fragile now than it has been in the past. Structurally, a lot more of today’s economy is in services where there is little of the kind of inventory buildup that can create lasting harm during a crisis. Similarly, the United States is less dependent on global trade than other developed nations, implying that disruptions in global trade and supply chains are likely to have a smaller impact.

Cyclically, the nation is in good shape despite the length of the current expansion. While the recovery from the Great Recession was long and slow, and overall growth remains slower than in past expansions, the fundamentals of the U.S economy are fantastic.

Pre-COVID-19, unemployment was at a 50-year low and in recent years labor shortages have been a problem in much of the nation. Both commercial and residential construction have had moderate runs with little sign of excess inventories. The pacesetter of consumer spending growth has been in travel, recreation, and restaurants. Business investment has been moderate. In short, nothing appears to be out of balance or due for collapse.

The financial economy, overall, is also healthy. Household savings rates are at a 30-year high, financial obligations ratios are at record low levels, and consumer debt markets have very low delinquency rates.

Debt burdens on U.S. households are lower now than they were in 2007 at the peak of the bubble or even in more normal 1998. Real estate has a close to record low debt-to-equity ratio and, thanks to changes in banking regulations following the Great Recession, borrowers in the last decade have had a median credit score above 750, the highest ever.

Corporate debt as a share of U.S. GDP is at an all-time high level, but the ratio of corporate profits to GDP also is close to record highs. And with such low interest rates, the aggregate debt burden on corporate America is actually quite low. The banking sector has great leverage, has been lending conservatively, and is enjoying close to record low loan delinquencies and losses. This is not a fragile economy.

It Looks Like a ‘V’

There is no doubt that the 10 million-plus people who are entering into unemployment will face a challenging period, even with expanded unemployment benefits and direct payments from the federal government. Many small businesses also are being pushed close to the edge as they wait to restart operations.

But among much of the consuming public, savings rates are good, debt burdens are low, and consumers are maintaining their earnings. For this group, the inability to spend money during the public health-mandated shutdowns will lead to a surge in savings and significant pent up demand. While some households will not be able to spend as much post-pandemic, others will likely spend considerably more than usual. The same applies to businesses and investors.

All this does not suggest a “U,” but a very large and rapid “V.” The second quarter will definitely post record negatives, but that will be followed by record positives in the last half of the year as we quickly return to normalcy.

We see GDP growth as follows: 0% in Q1, -30% in Q2, 25% in Q3, and 5% in Q4, with unemployment falling back to the low 4’s over the year. Not all the damage will be erased, but much of it will and things should largely return to normal faster than many expect.

Indeed, we may find that the second quarter will be the only negative growth quarter of the year, which will cause plenty of debate over whether this was or wasn’t a true recession.

It is also worth discussing the chaos that overran the financial markets in recent weeks—led by the collapse in the equity markets. The problems stemmed less from economic realities and more from financial improprieties. After the early 2019 sell-off, the market exploded upwards and at the start of this year, price-earnings (P/E) ratios were at 31—the third highest on record, topped only in the years 2000 and 1929, according to Robert Shiller’s index.

Maybe it will ultimately be a positive that this bubble was popped before it began to do harm in the broader economy. But the recent wild swings in the numbers cause havoc in short-run debt markets and put substantial, unnecessary strain on an economy dealing with a very real pandemic.

The Fed has now injected trillions of dollars into short-term credit markets, but it looks like much of the panic has already passed. Credit markets are settling down and the economy will, in the short term at least, enjoy record low interest rates along with lower gas prices and all the other benefits that come from falling commodity prices. This will also help with the third quarter bounce.

The larger question, however, is at what point will regulators finally begin to seriously address the excessive volatility of the financial markets over the last decade? The markets are supposed to be the shock absorber for the U.S. economy, but have turned into a shock expander.

Wildcards

While we believe that the most likely outcome for the U.S. economy is better than what most forecasts are currently suggesting, we must also be humble in the face of such an unprecedented shock. In this case there are two major wildcards.

• The first, of course, is the virus itself. They are wily things and can take strange and unanticipated twists and turns. If the spread of the coronavirus should spiral out of control again, public health mandates will once again take over and more damage will be done.

But even in such a case, public response should be faster and more forceful the second time around, allowing us to weather the storm better. The global population has experienced a big learning curve and we are likely to continue behaving vigilantly, which will help limit negative outcomes.

• The second wildcard is whether there will be a dramatic shift in consumer behavior after the pandemic ends. Certainly, people will wash their hands more often and handshakes may well become a thing of the past, but will consumers stop going to ballgames and music festivals? Will they be too afraid to go to restaurants?

We can’t really know, but it is worth noting that for hundreds of years people have faced pandemics that were far deadlier and more frightening than this one because they didn’t have the science or the medical responses we have today. Nevertheless, when there weren’t pandemics, or they ended, people continued living active lives. Even during wartime, or in places that are under constant threat of terrorist or other attack, people don’t allow low odds to halt their enjoyment of life.

This is not a new normal—it is a return to one that has been with us for a long time.

While we believe a “V” recovery is ahead, we say so very cautiously, and hope the false narrative that the “cure is worse than the disease” is not allowed to push us off our current path.

The California Chamber of Commerce Economic Advisory Council, made up of leading economists from the private and public sectors, presents a report each quarter to the CalChamber Board of Directors. The council chair is Christopher Thornberg, Ph.D., founding partner of Beacon Economics, LLC. The text of this report was first published on April 23, 2020. Graphics are a selection of those presented at the CalChamber Board meeting via Zoom on June 4.

The California Chamber of Commerce Economic Advisory Council, made up of leading economists from the private and public sectors, presents a report each quarter to the CalChamber Board of Directors. The council chair is Christopher Thornberg, Ph.D., founding partner of Beacon Economics, LLC. The text of this report was first published on April 23, 2020. Graphics are a selection of those presented at the CalChamber Board meeting via Zoom on June 4.