Despite the Narratives, California Is Doing OK

The U.S. economy entered 2024 at a good pace. Consumer spending continues to hum along, inflation has cooled, asset markets have surged to record high levels, and the pain felt in the banking and real estate sectors due to interest rates has been offset by surprisingly solid trends in construction.

All of this suggests that the current economic expansion will not end anytime soon. And as goes the U.S. economy, so goes California’s. As big an economy as California is from a global perspective (fifth or sixth, depending on how you count it), the state still accounts for less than 15% of total U.S. output. As such, good economic conditions at the national level will keep California’s economy moving as well. The key question revolves around the quality of that growth.

Regardless of the economic reality, popular narratives will undoubtably be negative, especially because this year we’re in the midst of a highly contentious presidential election. Both political parties will busily try to assert their particular narrative of the economy in their campaign messages — and blame each other for any and all ills.

Regardless of the economic reality, popular narratives will undoubtably be negative, especially because this year we’re in the midst of a highly contentious presidential election. Both political parties will busily try to assert their particular narrative of the economy in their campaign messages — and blame each other for any and all ills.

As much as the right likes to use California as their favorite example of what is wrong with the left, the left goes out of their way to paint California as an example of everything that is wrong with the right. In the left’s narrative, out-of-control capitalism is to blame for rising inequality, homelessness, falling living standards, and a degraded environment.

Beacon Economics’ opinion is significantly less grim than either. California is far from becoming the failed state that is so often depicted in headlines. Even a cursory look at the data illustrates how off base that doom and gloom narrative is. The state’s economy certainly has its share of problems, but the problems are fairly mundane rather than having any pointed political edge to them; and they are things that can be solved with some pragmatic tweaks to state policy.

Unfortunately, both sides’ priorities are far from what the state and its economy really need. This means that improving California’s course depends critically on fixing these broken narratives.

Social Narratives vs. Economic Realities

The narratives from both the left and right agree that California has big problems. According to a recent poll by the Los Angeles Times, over half the nation seems to think that the state is “in decline.” And who can blame them given proliferating headlines about budget deficits, population declines, rampant crime, the high cost of housing, one of the highest poverty rates in the nation, and the increasing number of homeless residents.

The difference between the right and left narratives is the source of the state’s problems. The right blames big government for turning California into a “socialist hellhole” where high taxes and heavy-handed regulations are driving people and business out of the state. The left blames the avarice of big business for turning California into a “capitalist hellhole” defined by inequality, housing insecurity, and rampant exploitation of workers.

The question is which one is the real culprit? Unfettered capitalism, or unfettered government? They can’t both be right!

The answer is that neither are accurate because the initial premise is wrong. Let’s start with the statistics.

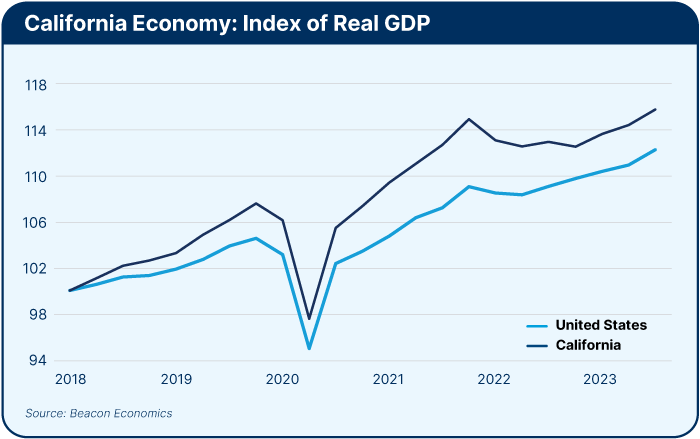

The annual benchmark revision from the Employment Development Department revised California’s 2023 jobs growth sharply downward. It now appears that payroll jobs in the state have grown only by 2.1% over the past four years (just prior to the pandemic) compared to 3.7% in the nation as a whole.

On the other hand, California’s real private sector output grew by 10% over the same period, compared to just 8% in the nation overall. This means less growth on the extensive margin and more on the intensive, through greater worker productivity.

Income data certainly supports this finding. California’s median household income grew by 9.2% from 2019 to 2022, compared to just 8% growth in the nation overall. Median incomes in the state are now 14.3% higher than in the nation as a whole — the largest gap ever in this data.

The U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) Quarterly Census of Employment and Wages (QCEW) data shows that average weekly earnings in California are 20% higher than in the nation overall and have grown 23% in the last four years.

However, none of this should imply that the state is doing great, or even well, from a historical standpoint. California has historically grown much faster than the nation overall, so just keeping up with the nation is definitely a downshift in trend.

We think it’s fair to say that California’s ability to expand its payroll employment by 2% over the last four years is actually impressive. That’s because during the same period the labor force contracted by 2%. Having more jobs with fewer working people is a nifty trick.

There is always a gap between payroll and household employment, driven by the self-employed who don’t show up in traditional payroll records along with some other subtle differences in how the two sets of data are gathered. This gap has been shrinking rapidly in recent years, a sign that fewer workers are self-employed, and more hold formal payroll positions.

California, particularly the coastal economies, saw a dramatic decline in labor force during the pandemic, driven primarily by an enormous wave of retirements. Growth has been slow since that time; over the last year the labor force in the state has increased by just 0.6%. As with income, the interior parts of the state have seen better overall trends, but even there, in recent years, the numbers have been sluggish.

The reason the labor force is not growing is the key issue, and that simply boils down to the low number of housing permits issued in California. A workforce cannot grow if there is nowhere for workers to live.

California Inequality

The narrative from the left will posit that the positive income and output numbers, and the contextually decent jobs growth numbers, don’t account for California’s widening inequality, inflation, high housing costs, and record levels of poverty.

The picture often painted by ideologically driven university labor centers and other advocates is downright Dickensian. In their narrative, unfettered capitalism is to blame for California’s woes, with helpless tenants subject to the wanton abuses of landlords and workers beset by wage theft and inadequate pay. The homeless are painted as refugees of this dystopian economy. Any overall economic gains are always at the expense of the bottom 50%.

But again, a bit of context changes the story… a lot. It seems almost self-evident that worker earnings in the state have not kept up with inflation given how often that claim is made by researchers and political leaders and reported by the media. The problem is it isn’t true.

The official BLS data on consumer prices in the state show a 20% increase from the end of 2019 to the end of 2023. As noted above, data from the Bureau’s QCEW payroll records show that average weekly earnings for California workers rose 23% over the same period; real incomes have actually increased in California over the past four years, as well as over the past 14 years.

More importantly, data from the U.S. Census American Community Survey shows that earnings growth has been greatest among lower-skilled workers in California over the past six years.

In other words, lower-skilled workers are seeing a higher pace of earnings increase. This isn’t purely a function of the state’s higher minimum wage; on this front, California’s trends mimic national ones. Income inequality is still high, too high, but it is finally falling in both the state and the nation overall.

We can see this across California. Some of the households that are enjoying the most rapidly growing median income are in lower-income regions of the Central Valley, including Madera, Tulare, Merced, Fresno and Kern counties. Indeed, the inland parts of the state are also seeing some of the sharpest increases in local spending at restaurants and hotels, according to taxable sales records.

We can also see these trends elsewhere. From 2019 to 2022, the average poverty rate in California was 12%, lower than the national average and the lowest level ever seen in the state. This is all good news, even though there is still serious work to be done to decrease inequality.

Yet, instead of heralding such positive news, advocates on the left simply move the goal posts, ensuring their “miserabilist” narrative remains intact.

One example is the use of the new supplemental poverty rate as opposed to the official poverty rate. The supplemental rate accounts for benefits received and also certain local conditions, such as the cost of housing. U.S. Census data shows that California’s official poverty rate is 11.4%, whereas its supplemental rate is 13.2%.

Using the new supplemental metric, California has the highest poverty rate in the United States, which sounds ominous. In actuality, it’s not that much higher than the official rate; the real shift is how this new supplemental poverty rate goes down in other states, increasing California’s ranking. Moreover, by either metric, California’s poverty rate is at a record low.

None of this should suggest that there aren’t struggling families and stubborn pockets of poverty across California — there are and always will be. But the trends are moving in a positive direction, something you’d never guess given the shrieking negative headlines.

Singing the Housing Supply Blues

California has long been infamous for its high housing costs, and homelessness in the state is constantly used as evidence of a housing crisis. Yet, even on this issue, a closer look at the data presents a more nuanced picture.

Start with rental housing. While it’s true that in 2022 the median rent-to-income ratio in California was the fourth highest in the nation at 32.7%, this isn’t quite as bad as it sounds. That ratio is actually slightly lower than it was in 2017 when it was 33.2%, despite the 32% increase in asking rents for vacant apartments. This trick was achieved because paid rents don’t rise as fast as asking rents, and because of the increase in income discussed above.

Start with rental housing. While it’s true that in 2022 the median rent-to-income ratio in California was the fourth highest in the nation at 32.7%, this isn’t quite as bad as it sounds. That ratio is actually slightly lower than it was in 2017 when it was 33.2%, despite the 32% increase in asking rents for vacant apartments. This trick was achieved because paid rents don’t rise as fast as asking rents, and because of the increase in income discussed above.

And as for California’s fourth place ranking, Texas, as a point of comparison, is middle of the pack with a rent-to-income ratio of 29.2%, just 3.5 percentage points less than California (that’s not much). And although rents in Texas are cheaper, incomes are lower as well. The median California renter earned $65,000 in 2022, whereas the median Texas renter earned $50,000. This implies that after paying rent, the median Californian renter was still $8,000 ahead of the median Texan renter.

As for home prices — for once, a U.S. housing bubble doesn’t seem to be a predominantly California issue. The Dallas and Houston metros have seen their median home prices rise by half again the rate of California’s metropolitan areas over the past five years.

This then begs the question — if housing affordability isn’t that bad, how do we explain the exodus of people from the state and the lack of labor supply? In 2020, California’s population peaked at 39.5 million and over the next three years it declined to slightly over 39 million, a drop of roughly one-third of one percent per year — not a big falloff; but back in 2000, the state expected to have 50 million residents by 2020. Since those heady days, population growth has continuously slowed, and ultimately the state didn’t even hit 40 million before the modest declines began.

The slowing of growth has been driven both by more out-migration and by a decline in the pace of natural increase, which is propelled by falling birth rates and the aging of the California population.

But overall, the recent population decline has been driven largely by an uptick in out-migration of state residents, described by many as “fleeing” the state in some sort of mass exodus.

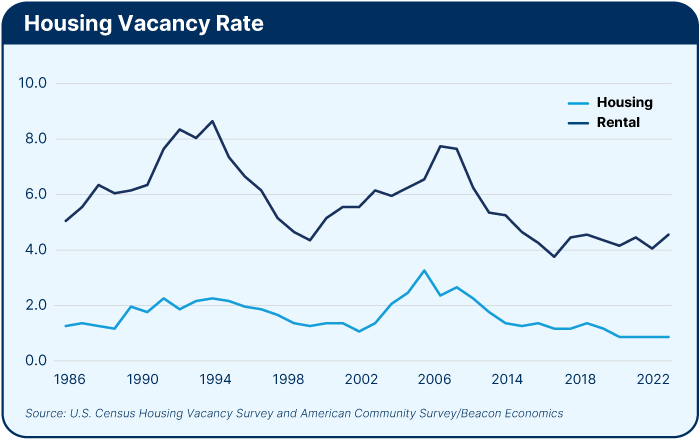

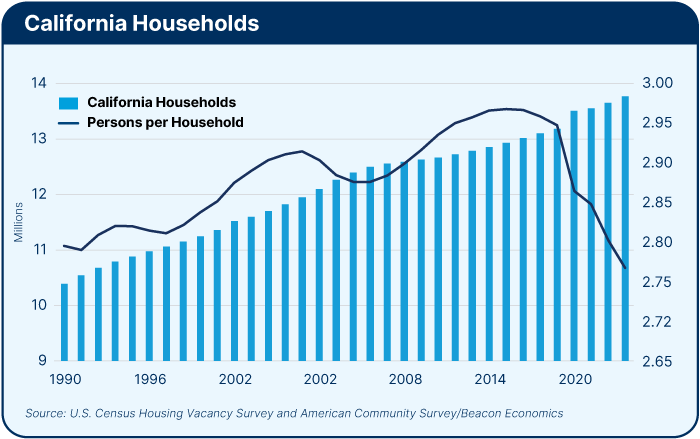

While the number of people living in California has fallen slightly, the number of households in the state has actually increased, and overall housing vacancy rates are at an all-time low level, according to the U.S. Census Housing Vacancy Survey and American Community Survey, and according to data on listings and apartment vacancies.

What is actually happening is that the state has seen a sharp decline in people per household over the last five years, falling 6% from 2.96 to 2.77 persons-per-household. Given that housing supply doesn’t expand that rapidly, by definition, a portion of the population must be pushed out. By pushed, we mean that the price of housing will rise to the point that some residents will choose to move out of the state.

What explains the decline in people per household? Many things. Families with children are more price sensitive to housing costs than those without children. Families with kids are moving out, those without are moving in. Also, a significant fraction of the overall population decline in the state is among people under the age of 24.

Still another part of the issue is rising incomes, which encourage people to spread out, living with fewer roommates, or even living alone. Typically rising rents encourage trends in the other direction — but it isn’t working this time.

Regardless of the cause, the only way to deal with the state’s population decline is to sharply expand the pace of new housing supply. But despite all efforts, the number of new building permits remains at the same tepid rate of 120,000 per year it has been at for the last decade. This is far fewer than what the state used to build.

Dealing with the Budget Blues

The most immediate issue facing California is its budget deficit, which is running somewhere between $35 billion and $70 billion, depending on who you ask. And this is occurring less than two years after the state was bragging about its $100 billion surplus.

The surplus was driven by California’s high marginal tax rate on high-income earners.

In an average year, income taxes make up 25% of California’s revenues. In fiscal year 2022–23, when the state supposedly had a massive surplus, they constituted a full two-thirds, with capital gains realizations reaching twice the level of the previous two bubbles.

The good news is that the economy is healthy, implying that revenues from other sources are still strong and thus helping the problem. And unlike the last two bubbles, this time asset prices have not collapsed, but instead appear to have plateaued for now. This circumstance will keep some portion of capital gains coming in.

Conclusion

The budget deficit notwithstanding, California’s economy is doing fine today and will continue to grow in the near future. But the inability to genuinely tackle the state’s housing supply issue is slowly halting the mighty California economic machine. Instead of leaning into this one entrenched and tremendously consequential issue, state regulators and policymakers continue to veer off on quixotic missions to fix problems that exist in artificial narratives, not in reality. In doing this, they create new problems that will inevitably slow the economy even more. To fix the economy, we must first fix the narrative. Sadly, in today’s environment, accomplishing that feels like a distant dream.

Staff Contact: Nicole Wasylkiw

This economic outlook report is adapted from the special report presented to the CalChamber Board of Directors by Christopher Thornberg, Ph.D., founding partner of Beacon Economics.