The Economy

The Drumbeat of a Recession Is Growing Louder, But It Is Probably Not Here Yet

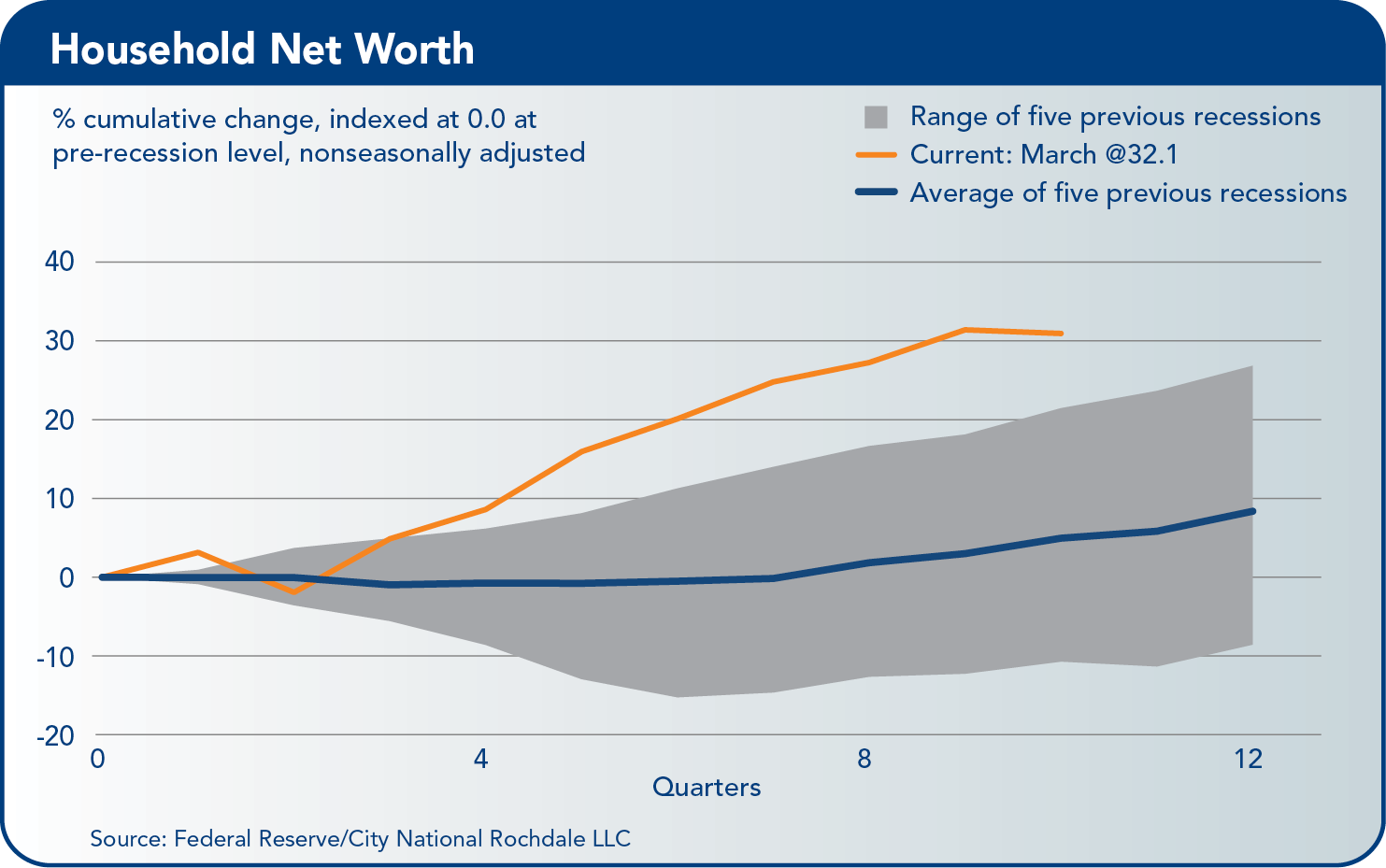

We are sure in an odd place, economically speaking. Job growth is solid and households keep spending money. Yet the world seems to think we are in a recession.

Question: What is the opposite of a jobless recovery? A recession without layoffs? Is that a recession? We are also in a quirky time with data continuing to be volatile due to the ebbs and flows of consumption and supply chain disruptions from the pandemic.

The news seems to focus on the risks of the economy being in a recession or soon to enter a recession. This can be seen in the number of people asking that question to Google, which has skyrocketed.

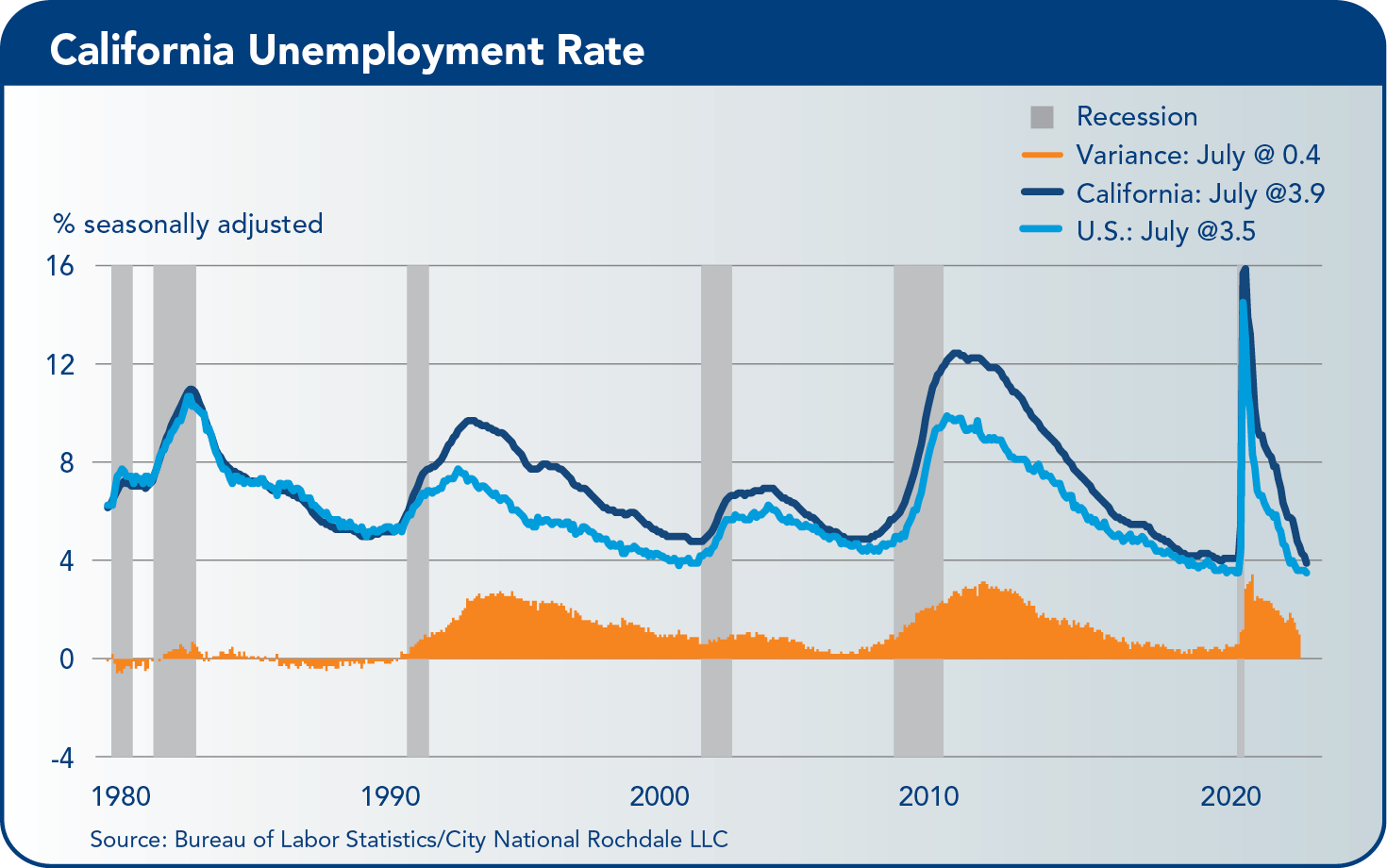

It is higher now than in the past two recessions, but in the past two, it was pretty obvious since there were massive increases in the unemployment rate. This time is more confusing since the unemployment rate is falling.

It is not officially known whether the economy is in a recession. The National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) is the self-appointed arbiter of the American business cycle and has been dating recessions for almost a century. They are precise with the start and end dates of a recession, but they are not timely when announcing when a recession happens.

They need to wait for the release of economic reports and revisions before they make a decision. They take a deliberate retrospective approach, so they do not have to revise. Since 1980, there has been an average of 7.2 months from the start of the recession to the NBER announcement.

The NBER defines a recession as a significant decline in economic activity spread across the economy, lasting more than a few months. It is usually visible in real gross domestic product (GDP), real income, employment, industrial production and wholesale-retail sales.

Three of the six indicators they follow are directly related to the labor market. The others deal with income, spending and manufacturing. For the past three months, five of these six indicators have been in the positive territory. So although many may think the economy is in a recession, it probably is not now.

That said, the pace of growth of these indicators has been slowing. But slowing is not contracting. The important question is where the economy is headed. Is it transitioning to a slower, more sustainable pace or to a contraction?

Complicating the outlook is the Federal Reserve, which is firmly committed to reducing the high pace of inflation by raising interest rates by another 100 basis points (bps) by year-end. This will put the funds rate above the neutral level and well into the restrictive territory. With the Fed actively trying to slow the pace of economic growth, the path to a soft landing is becoming narrower, and the risk of a recession continues to grow.

Labor

If the U.S. Economy Is in a Recession, No One Seems to Have Told Employers

The unemployment rate stands at 3.5%, reaching the lowest level since February 2020 and tying for the lowest rate since 1969.

Payrolls have surpassed the previous record high just before the pandemic; they now stand at 152.5 million, 32,000 above the previous high.

So far this year, payrolls have increased 3.6 million. That is higher than the average of a good year of growth, and there are five more months of data to go.

Inflation

Inflation

The Fed’s Fight Against High Inflation Is Not Over

The drop in inflation this past month was welcome news and offers hope that inflation may begin to cool off going forward. The yearly change in the consumer price index (CPI) fell to 8.5% in July after hitting a 40-plus-year high of 9.1% the month before. This change in the inflation trajectory is good news for consumers, businesses and the Fed, which has labeled inflation as “public enemy No. 1.”

Lower energy prices were the driving force behind the decline in inflation and are on track to make a more significant drop in the August CPI report. The July report saw prices fall about 40 cents in the cost of a gallon of gasoline. For the upcoming August report, there will be a decline of about 60 cents (the CPI report measures changes from mid-month to mid-month).

But the decline in inflation is not in response to the Fed’s actions of reducing monetary stimulus. The Fed has very little control over energy and food prices. The drop in energy prices represents the slowing in global demand as the pace of growth slows.

As for food prices, they continue to be a problem. In the past year, they have increased by 13.1%, the highest rate since 1979. A surge in fuel and fertilizer prices started the upward pressure in food prices. But prices have since been affected by a series of supply shocks (drought in the South and West that pushed up meat and fresh vegetable prices, the avian flu outbreak in the Midwest that caused a spike in the price of chicken and eggs, and the war in Ukraine that caused corn and wheat prices to surge).

Fortunately, the shocks are beginning to unwind. This is showing up in the falling of spot and futures prices of many of these food commodities. That is a start, but a significant portion of the cost of food is transportation, packaging and labor. Those costs haven’t retreated as much, so the expected decline in food prices in the CPI calculation will be slow.

Despite the price decline of the highly volatile component of energy putting inflation on the downward path, and the fact that food inflation is expected to be the next shoe to drop in the deflation story, the Fed still has concerns about inflation.

They are worried about the components that are not as volatile, what is called “sticky inflation” — items that don’t tend to fall in price when demand slows (for example, a haircut, cell phone, medical care, etc.). These prices represent about 70% of CPI and are still on an upward trajectory. The rate above 5.0% is well above the Fed’s comfort zone.

So the Fed will continue to keep upward pressure on the federal funds rate until it has seen clear evidence of a sustained slowdown in inflation.

The Fed

The Next Hike in Rates Will Probably Be 50 Basis Points (bps)

The Fed has now raised the federal funds rate four times in this cycle, increasing it by a total of 225 bps from 0.125% to 2.375%, in an effort to corral soaring inflationary pressures. They are raising interest rates at the most aggressive pace since the 1980s. The recent move of 75 bps is the second in a row and matches the largest increase since 1994.

The Fed has little choice; they have taken a bare-knuckled approach to fighting inflation. They are determined to slow the pace of economic growth because inflation recently hit a 40-year high of 9.1% year over year.

Since the Fed started raising rates back in March, economic indicators of spending and production have softened. But at the same time, job gains this year have been strong and the unemployment rate remains near the 50-year low of 3.6%.

That said, the Fed downgraded its assessment of the current state of the economy. The Fed is also benefiting from the growing belief that the global economy may enter a recession. This has helped drive down the price of many commodities like oil, gasoline, wheat, corn and copper.

Although the public may seem worried that the economy may soon enter a recession, Fed officials see it differently. They believe the strong labor market will allow the pace of economic growth to continue to grow despite the higher level of interest rates, what they call a soft landing.

With the funds rate in the neutral range, managing monetary policy now gets tricky (back when interest rates were at 0.125%, raising rates didn’t have much of an impact, since they were still in the stimulative range; now future hikes will be in the restrictive range). Aside from a spike in inflation, the Fed may start opting for smaller interest rate increases going forward.

The Fed will want to tread carefully and see how the economy responds to their actions. Since monetary action takes an estimated 12–18 months to affect the markets, the slower pace of raising rates will mitigate the risk of overtightening — this would mean the Fed is moving into the “data dependency mode.”

The impact of Fed actions has already been seen in the housing sector, one of the corners of the economy most sensitive to interest rates; sales are beginning to slump.

This economic outlook report to the CalChamber Board of Directors was prepared by Paul Single, managing director, senior economist, senior portfolio manager, City National Rochdale.

This economic outlook report to the CalChamber Board of Directors was prepared by Paul Single, managing director, senior economist, senior portfolio manager, City National Rochdale.