The Great Un-Recession

When we look back at 2019 there will be plenty of negative memories—from the theatrics that have dominated national politics to the ongoing trade war with China to the unnecessary crisis of confidence that exists within our borders to grim tidings on the international front as the result of a slowing European economy to deepening political crises in the Middle East.

Despite all the turmoil, what will not make the list of “2019 negatives” is the health of the United States economy. Pessimistic press coverage and punditry aside, the sum total of indicators for the year shows that the U.S. economy is continuing to grow at the same steady, uninspiring rate that has now become the hallmark of the longest expansion on record. More importantly, there is little sign of any collapsing imbalances or rapid shifts in aggregate demand that would presage economic issues in the year ahead.

This shouldn’t imply that there aren’t a number of stressors and strains on the economy—only that they do not add up to the kind of shock that is capable of pushing the U.S. economy into a downturn or even a protracted slow growth slump. Beacon Economics continues to see 2%-plus real growth in 2020, and up toward 2.5% in 2021.

This outlook leaves us on the bullish side relative to many of our forecasting peers. As of November, a plurality of economists who contribute to the Wall Street Journal’s Economic Forecasting Survey (34%) still believe there will be a recession in 2020. It should be noted, however, that in November 2018 more than 60% of the Journal’s forecasters predicted there was going to be a recession in 2020. In 2017, they predicted the recession would hit in 2019. In short, such surveys have little predictive value.

The primary risk to the short-term health of the U.S. economy is nothing that is in play at the moment. But in this era of hyper-partisan politics combined with a besieged president who has the capacity to decree large changes in economic policy on a whim, we have to maintain vigilance.

Even as this outlook is being written, threats are emerging that new tariffs may be levied on imports from France, Argentina and Brazil. However, the validity of such rhetoric has to be considered seriously as these kinds of hyperbolic statements without actual action have been par for the course under the current White House administration. Then again, this administration has followed up with action enough times to keep us wary.

Looming Issues

But while the nation unnecessarily flirts with short-run disasters, the looming issues of long-run economic health—dealing with the health care cost crisis, the desperate need for pension and entitlement reform, and reversing dangerous trends in wealth inequality, among others—remain largely ignored. This will come back to haunt us eventually—the only question is when, not if.

Beacon Economics’ current outlook, as always, begins with the structure of gross domestic product (GDP) growth. What is most notable about the data is just how steady growth has been despite all the frantic headlines.

U.S. GDP growth was 2.8% in 2017, 2.5% in 2018, and has averaged 2.4% for the first three quarters of 2019. Throughout this entire time period, consumer spending has been the primary driver of growth.

Last year, weakness in trade and residential investment was offset by strong business investment. This year, business investment has slowed, but strong growth in public spending, with better results in residential real estate and trade, is functionally making up the difference.

Much of the confidence surrounding the ongoing health of the U.S. economy sits with the consumer. The brief lull in spending growth that occurred at the end of 2018 reversed itself by the end of the first quarter of 2019. Consumer spending is now growing at roughly the same pace as U.S. GDP.

Overall, low interest rates and slow borrowing have kept the financial burden on households at record low levels for a number of years. Moreover, recent declines in interest rates—from where they were at the end of 2018—will lessen the burden further.

Falling interest rates also are the reason that the nation’s housing market is starting to bounce back. Sales of new and existing homes are up, home price appreciation is beginning to accelerate, and the third quarter saw residential investments contribute to overall growth. This was all fairly predictable, as noted in the last few editions of this outlook.

After all, none of the conditions for a major housing bust were in play. Instead, we’ve seen clean mortgage lending, no excess supply being built, and increases in overall affordability as measured by the housing cost share of income for U.S. households.

Tight Labor Markets

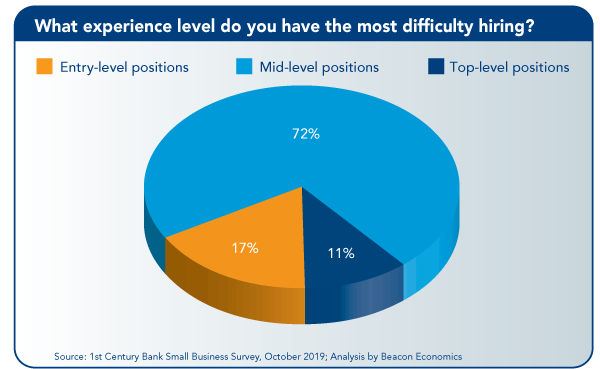

This is all being supported by record tight labor markets in the United States. The national job openings rate has been higher than the unemployment rate for two years now. Competition for scarce labor resources has led many workers to receive a significant increase in earnings, and a growing share of national income.

In 2014, compensation for employees was 60% of national income, compared to 63% in 2019. And it isn’t just high-skilled workers who are enjoying the gains. According to data from the U.S. Census American Community Survey, workers without a high school degree have seen their pay increase by 15% since 2015—twice the pace of workers with college degrees.

Interestingly, most of this income has shifted from corporate profits, which fell from close to a record high of more than 14% of all national income in 2014 to less than 12% this year. Nominal corporate profits were flat over this time period. But this masks the reality that domestically profits have fallen sharply and have been balanced out only by an increase in overseas earnings.

While this contradicts the record high price levels equities are currently commanding, calling the market mispriced is substantially different than predicting large declines in values in the near term. As Keynes wisely noted, the market can stay irrational longer than you can stay solvent.

More important, this overpricing doesn’t seem to be driving any real imbalances in the broader economy; hence a big decline in values is unlikely to have a large negative impact on U.S. GDP growth the way it did in 2000. Indeed, business investment has not kept up with stock market values the way it did in the late 1990s.

As noted, the one weak spot in the nation’s GDP data in 2019 was in business investment. Spending is down in that area for any number of specific reasons, but not too many general ones. Pullbacks in investments in mining are being driven by low market prices for oil and declines in investment in transport equipment can be traced to problems at Boeing.

U.S. Exports

Weak export data has also played some role in slowing investment. But the overall impact of the trade war with China has been highly overstated. While it’s true that both imports and exports of products to China have fallen sharply in the last two years, the overall value of U.S. imports and exports is roughly the same as it was two years ago. The United States is simply buying and selling more with other nations.

The biggest issue for U.S. exports isn’t China, but rather a U.S. dollar that hasn’t been this expensive in global currency markets since 2002. Indeed, alongside a weak global economy, the dollar’s value actually illustrates the resilience of the U.S. economy overall.

The strong value of the U.S. dollar is in part being driven by higher interest rates in the United States as compared to much of the developed world. This is one of the reasons President Donald Trump has consistently criticized the Federal Reserve’s slow pace of rate reductions relative to many other central banks around the globe.

Money Supply

While Beacon Economics strongly disagrees with the idea that rates need to go back to near 0, we have always been perplexed by the decision to raise rates so aggressively in the first place. There simply hasn’t been sufficient growth in the money supply to allow for inflation. Indeed, weak M2 growth is why the Feds had to intervene and inject billions into the overnight inter-bank lending markets a few weeks ago. There is no reason to cool an economy that is not overheated in the first place.

Now the Fed is loosening, not to help the economy, but rather to unwind the yield curve that dipped into negative territory in August 2019. Putting further stress on a banking system that is already dealing with excessive limitations from Dodd Frank is definitely something to avoid.

It isn’t that the United States is suffering from a lack of lending, but regulatory constraints on banks have pushed more lending into the less regulated parts of the industry—and there are growing signs of excess risk taking place in such markets. Again, such stresses do not represent any current threat to the U.S. economy, but may turn into a threatening imbalance in the future.

All in all, at its current steady pace of growth, it seems unlikely that the real economy will play much of a role in the 2020 presidential election cycle. But this is not likely to dissuade candidates from making their miserabilist pronouncements about the economy’s health.

The disconnect between simple economic realities and political rhetoric is growing wider—and this may be the most dangerous trend of all. The less connected policymakers are from reality, the more likely their policies will hurt more than help.

California Outlook

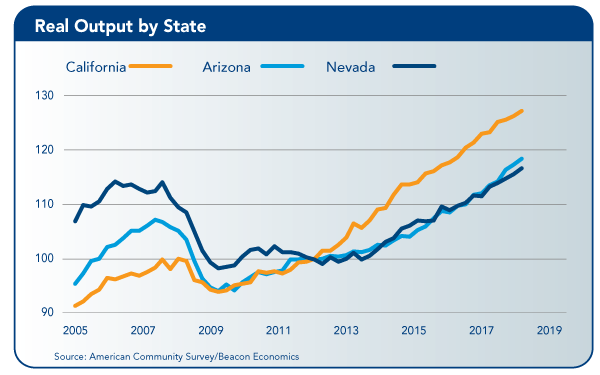

Despite a nagging perception that there are murky clouds on the horizon, California’s economy reached a number of significant milestones in the most recent quarter. The state’s unemployment rate dipped to 3.9%, which represents a new record low, and employment and wages both reached all-time highs.

The longer the current expansion persists, the closer we are to the next recession, but business cycles do not die of old age, and at present, there are few signs of a slowdown in the state’s economy.

Employment Keeps on Soaring

Since October 2018, California’s economy has added 308,000 jobs, which is equivalent to a 1.8% year-over-year increase, exceeding the nation’s growth rate of 1.4% over the same period. This rate of growth is well above the state’s long-term employment growth rate, which has averaged 1.2% per year since 1991.

Within the state, we see considerable variation in job growth rates by region. While Los Angeles has added the largest number of jobs over the last year, this is primarily a function of its size. As the largest region in the state, even a small growth rate in Los Angeles will add up to a large number of jobs relative to a region that has a high growth rate but is home to a smaller number of overall jobs.

Indeed, Los Angeles experienced a slower growth rate than many other parts of the state. The most impressive growth rate occurred in Merced, where we see the opposite effect—namely, in smaller economies the addition of a relatively modest number of jobs can inflate growth rates.

Perhaps the most impressive performance within the state occurred in the San Francisco Bay Area. Job growth in the Bay Area was remarkable, especially given the region’s size. Together, San Francisco, San Jose and Oakland added jobs at a rate of 2.99%—more than double the national rate—and accounted for one-third of California’s job growth over the last year.

Broad Sectoral Strength Continues

Fully 40% of California’s job growth over the last year was concentrated in just two sectors: Health Care and Social Assistance, and Leisure and Hospitality. Different factors are driving growth in each of these sectors. Secular trends, such as a growing elderly population, account for growth in Health Care and Social Assistance employment.

Growth in Leisure and Hospitality employment is a sign of a strong economy as it reflects underlying strength in the health of the consumer. The more confident consumers feel, the more likely they are to travel or dine at a restaurant. Growing wages and high home prices also add to the consumer’s strength and contribute to sectoral job increases.

Strong job growth also occurred in Government, Construction, and Professional and Scientific Services; however, the Retail Sector remains a dark spot in the state’s economy. The reasons for the trouble are widely understood. Competition from online retailers has hit certain parts of the retail sector hard. This is especially true for department stores, which lack the flexibility and dynamism to compete with their online counterparts.

Against this generally sunny picture, California’s labor force is a cause for concern. The state’s labor force peaked in February 2019 and growth turned negative in August of this year. While it’s not advisable to read too much into a few data points, the cost of living in California and the rate of new home supply are among the key factors that weigh on the labor force growth rate.

Signs of a Housing Slowdown? Not Quite

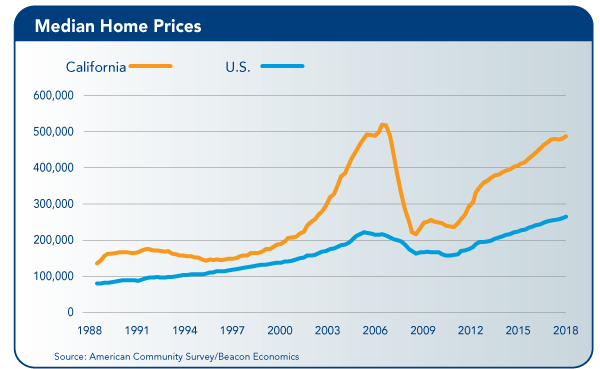

As always, the health of California’s housing market consumes considerable bandwidth in public discourse. State and local leaders are absorbed by the topic, while new entrants to the market bemoan home prices. Despite suggestions to the contrary, home sales in the state remain strong. The rise in interest rates in 2018 placed a drag on sales, but rates have fallen this year and home sales have rebounded nicely.

Home price growth, however, has shown some signs of exhaustion over the last year. The median price for a single-family home in California grew 2.2% over this period, which when adjusted for inflation, means that price growth has effectively been flat.

To place this figure in context, since 2010, the median home price in the state has doubled, and such a relentless pace of appreciation cannot continue unabated. To be sure, lower interest rates should spur home price growth in the state, but it’s unrealistic to expect the rate of growth we’ve seen in recent years to continue.

Home prices in some markets have become particularly overstretched and drawdowns in the median home price have occurred in some locations. Over the last year, the median home price fell by 4.1% in San Jose, while real home price decreases occurred in other major markets, including San Francisco, San Diego and Oakland. Real home price growth was effectively flat in Los Angeles.

Again, after the run up in prices that has occurred in recent years, such a slowdown is perhaps not surprising. When the median home price in San Francisco stands at $1.4 million, the room for sustained price inflation is limited, no matter the strength of the local economy.

The extended home price growth that has occurred in some regions also can spur growth in other parts of the state. Home price growth in less expensive areas, particularly in the communities of the Central Valley, has seen impressive gains, fueled by historically low interest rates and their affordability relative to coastal communities.

The issue of home building permits is, however, a cause for concern. The supply of building permits peaked in the first quarter of 2018, and permit growth turned negative in the third quarter of that year. This growth has remained negative throughout 2019.

Constrained housing supply will continue to place upward pressure on home prices and also could limit growth of the state’s labor force.

Trade Woes

California’s exports and imports are both lower at this point in late 2019 than they were at the same time in 2018. Moreover, 2018 exports and imports were down around 10% compared to 2017. At present, this slowdown has not translated into a slowing of the state’s labor market, in part because the state’s economy relies so heavily on locally consumed services. But the continued unpredictability and whims of the Trump administration’s trade policy is far from an ideal setting for the state’s exporters.

Overall, the health of the labor market remains a pillar of strength for the state’s economy. While this strength continues, the outlook for the state’s overall economy remains strong.

The California Chamber of Commerce Economic Advisory Council, made up of leading economists from the private and public sectors, presents a report each quarter to the CalChamber Board of Directors. The council chair is Christopher Thornberg, Ph.D., founding partner of Beacon Economics, LLC.