In March of this year The Economist ran an article with the headline “California is gripped by economic problems, with no easy fix. Rising unemployment, a growing deficit and persistent outmigration are a painful trinity.” The article concludes that the state is a weak spot in the middle of an otherwise healthy U.S. economy.

Although the picture is more complex than the headline implies, there is little doubt that California is not doing as well as it has in the past. The only substantial argument is over why the state is faring so poorly, and the depth of the rot.

The dominant narratives from the right and the left of the political spectrum obviously differ in their explanations. Those on the right confidently say that the state’s “socialist” policies and overregulation are strangling the business sector. The left, on the other hand, just as confidently claims that the problems are a function of yawning inequality and the crushing burden of rising housing costs.

Misinterpretation

California is indeed facing some critical challenges, but these two very standard narratives largely misinterpret the causes and consequences of the problems.

First, these issues are not a sign that California’s economy is doing all that badly, and certainly not as badly on a number of dimensions as headlines would suggest. The state’s economy is growing, just at a slower-than-typical rate.

Second, a closer look at the issues highlighted by The Economist indicate that California’s problems relate to a number of unforced policy and fiscal errors, which have created a drag on the state’s ability to grow.

A change in approach would serve California well, but this can occur only if we align the narrative about the state’s economy with the reality.

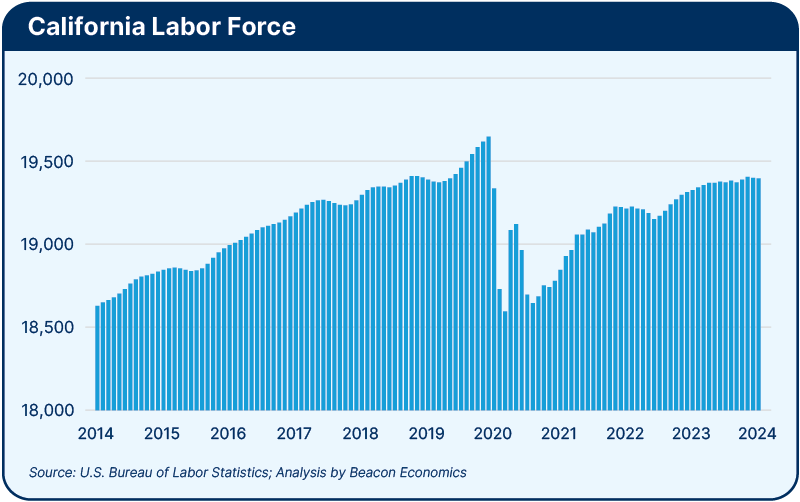

Labor Supply

A year ago, job growth in the state had stalled but, over the past year, has rebounded to a 1.2% growth rate. This is slower than the national average but given that California’s labor force declined slightly over the same period and is still below its 2019 level (19.2 million in May 2024 compared to 19.25 million in May 2019), it’s clear the issue is one of labor supply, not labor demand.

California’s job opening rate is still higher than it was in 2019 despite lower job growth, according to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. The state is being held back primarily by a lack of new labor supply, not a lack of labor demand.

The pattern of growth across the state reflects this basic issue: California’s economy is slowing because of a lack of workers. The regions that have added significant payroll jobs over the last two years, such as the Inland Empire, Sacramento, Fresno, and Stockton, are all located in less expensive inland parts of the state and are able to grow because of their expanding labor force.

In contrast, the more expensive coastal markets have seen much less labor force growth, and hence less payroll job growth. The differential impact on California’s coastal communities is a function of slower growth in their housing supply combined with a greater share of their labor market entering retirement.

Shifting Growth

California’s output and job growth data doesn’t show a state that has stumbled on hard times. Rather, the data reflects a state in which growth is shifting from the extensive margin to the intensive margin, as one might expect in a place that has seen no labor force growth in the last half decade.

This extensive-to-intensive shift in growth can be seen in the state’s per capita income data. Consider that California’s per capita personal income has been rising more rapidly than in the nation overall for a full decade. Per capita personal income in California is currently 17.5% higher than national personal income, or about 5% in real terms once we control for relative costs in the state. Yup, Californians are still doing better than the average person in the United States, at least on average.

The same conclusion can be drawn if we look at median household income or weekly earnings. Moreover, there hasn’t been a slowdown in consumer demand. Taxable sales in the state are still 23% higher than they were before the pandemic. The prices of goods that are taxed only went up by 11% over the same period.

Other Indicators

Some may retort that these averages do not reflect distributional differences; there is a wide difference in economic outcomes across the population and those at the bottom of the income spectrum may be suffering more than the average or median reveals. But even here, the evidence doesn’t indicate such a dismal state of affairs. Tight labor markets have boosted the earnings of lower-paid workers both in California and the United States overall during the past decade, reducing income inequality.

In 2022, the state’s poverty rate was 12.2%, slightly above where it was in 2019, but below any reading prior to 2018. In other words, it’s still close to a record low level.

A good proxy for more recent outcomes is the data from Equifax and the Federal Reserve on the share of the population with a sub-prime credit score, which is a metric that is highly correlated with poverty. In every part of California, this data shows that the share of population with a sub-prime credit score is lower than it was in 2019 and far below where it was a decade ago.

The share today is slightly higher than it was in 2022 but given how overheated the economy was in 2022 (as reflected by high inflation) this seems like a return to normality rather than a new negative trend.

Unintended Consequences

So, if California’s economy is doing OK, why is the unemployment rate going up, why does the state have such an enormous budget deficit, and why are people moving out? The answer to all three questions lies in the law of unintended consequences, consequences that have resulted from California’s poor policy choices over the last decade.

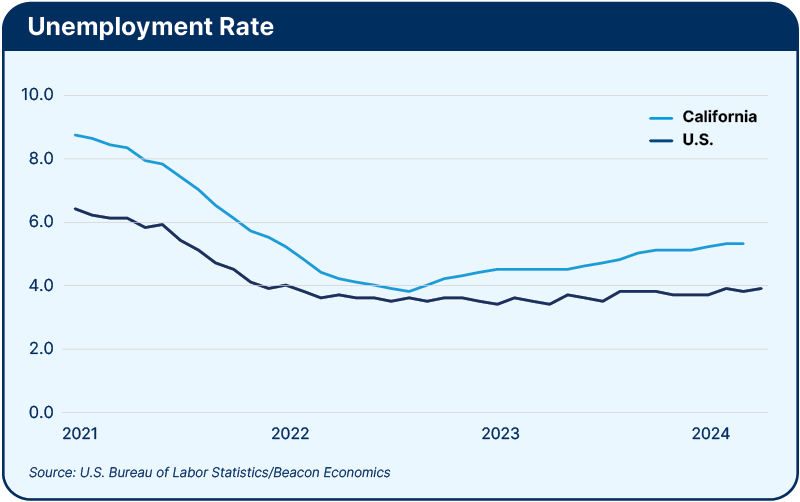

Take the rise in the unemployment rate which, as of May 2024, sits at 5.2%, up by more than one percentage point over the last two years and now the highest of any state in the nation. In contrast, the unemployment rate in the United States as a whole has risen from 3.7% to just 4% over the last two years.

The increase in California’s unemployment rate has occurred even though payroll employment has grown during the past year, and without any noticeable increase in the number of initial claims for unemployment insurance. Clearly, this rise in unemployment isn’t being driven by layoffs in the entertainment or tech industries.

Labor Market

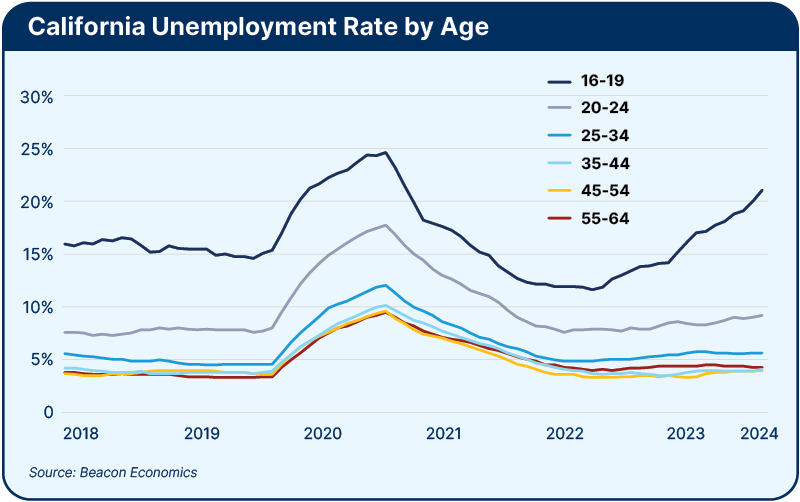

The cause may become clearer when we look at where the labor market is weakening. It turns out that the biggest increases in unemployment in the state are occurring among teenagers aged 16–19. The unemployment rate for this group has jumped from 14% to 23% in the last 12 months, compared to an increase of 10.8% to 12% for teenagers in the nation overall.

It also stands in contrast to the unemployment rate among 25-44 and 45-64-year-olds in California, which has actually dropped slightly over the same period of time. This is very unusual as changes in unemployment rates are typically highly correlated across age groups.

Though atypical, this pattern of employment change aligns well with how high minimum wages distort the labor market — something that Beacon Economics detailed in a recent white paper. California’s push to reduce income inequality through the use of wage floors is beginning to have a significant negative impact on some of the most vulnerable workers in the state’s economy — our youth, particularly those from lower-income households.

There are no gains left to reap from this policy — raising the minimum wage further will help some workers but only at the expense of many others.

California needs to reconsider its push to raise the minimum wage even higher this November, and instead focus on policies that do more to help lower-income households — and without causing unintended harm to other vulnerable groups. Such policies include early childhood education (universal preschool), adult workforce development programs, and expansion of the Earned Income Tax Credit.

Budget Deficit

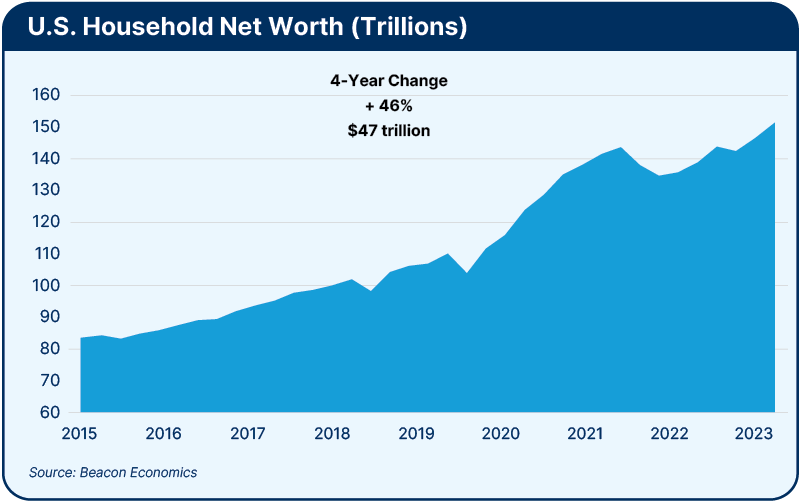

As for the state’s colossal budget deficit, that has been caused by the unforced error of sharply expanding spending on ongoing programs. These expansions have been based largely on the temporary surge in state revenues that accompanied the jump in asset values from 2020 to 2022.

This is the same problem that occurred during asset market surges back in 1999 and again in 2007, driven by California’s excessive reliance on income taxes collected from high-income earners. Currently, the state government’s spending out of the General Fund is above 7% of state personal income, which is the highest proportion the state has ever seen. In short, the deficit is a public spending problem and not a revenue one.

What about the issue of declining population? It’s what’s constraining California’s labor supply, and thus, preventing more rapid job growth and (likely) better revenue growth.

California’s household population has fallen by 360,000 in the last 5 years, representing a decline of slightly less than 1%. This drop is being driven primarily by negative net migration, meaning more people have moved out of the state than have moved in. However, California’s population size did hold steady from 2023 to 2024, suggesting the worst of the declines are in the past.

California’s Housing Problem Is About Supply, Not Affordability

But why are people leaving? Popular narratives about why Californians are fleeing the state vary across the political spectrum, with some claiming it is the rich trying to escape high taxes, and others saying it is lower-income families fleeing high housing costs.

These differences are irrelevant because people aren’t fleeing — they are being forced out. If people were leaving voluntarily, the housing vacancy rate would be rising.

However, the vacancy rate in California is not rising; it’s falling and currently sits at or near a record low level depending on which survey you use. For example, the state’s Department of Finance estimates the current housing vacancy rate at 6.4%, which is one percentage point lower than it was a decade ago.

More Households

How do we reconcile these two seemingly contradictory trends of a declining population and a declining vacancy rate? By recognizing that while the population has fallen, the number of households has increased. This in turn has been driven by a decline in the number of people per household.

The data on changes in California’s housing stock over the last decade show the number of people per household declined by 6.2% while the housing stock increased by only 6.7%. Hence, the state’s household population could have grown only by 0.5%, holding all else equal.

The extra 1% in population growth can be attributed to a decline in the vacancy rate. Essentially, the existing housing stock is being used more intensively than it was before.

For California’s population to grow faster and, in turn, for the state’s labor force to grow faster, there would need to be an increase in housing production — something the state has completely failed to do despite promises from Governor Gavin Newsom dating back to before his first term began.

The state continues to produce slightly less than 10,000 housing permits per month, which is exactly the same level as back in 2017. Despite all the changes to the Regional Housing Needs Allocation (RHNA) rules, despite SB 8 (a 2021 amendment to the Housing Crisis Act of 2019), SB 9 (The California HOME Act), changes in accessory dwelling unit (ADU) rules, and so on, California has simply failed to address its housing shortage.

And that is the critical issue — California’s economy is being held back by the state’s housing shortage, not by housing affordability. The failure to address the actual unit shortage and instead focus only on affordability misses the point and fuels gentrification.

As the lack of housing supply drives up home prices, higher-income families who enjoy lower price sensitivity are moving in, pushing housing prices up even further, and pushing lower-income families, who face greater price sensitivity, out of the state. Today’s market prices partly reflect the incomes of those moving in, which is why housing costs as a share of income have not really increased in the last decade. California’s higher housing costs reflect the higher incomes of both renters and owners.

Skewed Perspective

While the share of cost-burdened households is higher in the state than in the rest of the nation, it is worth noting that this metric delivers a skewed perspective on California’s housing value, and on housing value generally.

What is not apparent, but more relevant, is that the choice to live in California is a function of the income that is left over after housing has been paid for, not a function of the share of income spent on housing. Consider that net of housing expenses, the median Californian household that owns their home earned 17% more than the rest of the nation in 2016 and 21.2% more in 2022.

Californians make more money than residents in other states even after paying their high housing costs. For renters, the net-rent bonus for living in California has gone from 20.6% in 2016 to 26.9% in 2022. Despite the increase in housing costs, income growth shows that it is still worth it to move to California from a financial standpoint.

For those who live in California, the housing problem is not with affordability, but with supply. The lack of supply has forced prices up and compelled some residents to leave in search of more affordable housing. To prevent further exodus, the state needs to build enough new market-rate housing to meet incoming demand.

If California fails to do this, all existing and new affordable housing programs will be for naught; in sum, the market always wins. And this means, the state needs to go back to the drawing board and find effective solutions to increase its supply of housing units.

Misguided Regulations

The modest efforts to increase supply that have been enacted at the state level have been more than offset by sharp increases in state and local regulations. These well-intentioned but misguided regulations include limits on rental price increases, a widespread use of eviction moratoriums, a failure to prioritize market rate units for permitting, and even going so far as taxing the supply of new housing (so-called linkage fees) to subsidize incredibly expensive affordable housing units.

These types of regulations have more than undone any new supply that has been added. Incredibly, instead of pushing back on such counterproductive policies, or engaging in more stringent housing supply rules, California’s government, as well as various local housing interest groups, are proposing to expand rent control — a change that is far more likely to shrink housing supply than expand it. If rent control expansion passes this November, it will undoubtably cause another decline in permits, which will in turn lead to yet another surge in out-migration from the state.

Policy Stresses on Economy

In sum, California’s economy is doing fine — except where it is being stressed by policies that are well-intentioned but causing more harm than good.

Tight labor markets have helped lower-paid workers significantly, but the insistence on pushing the minimum wage up to ever higher levels is starting to have a negative impact on some of the state’s most vulnerable workers — teenagers looking for entry-level jobs.

The budget deficit has been driven by a sharp expansion of ongoing social support programs, something that has occurred even though earnings among lower-income households have been on the rise and poverty rates are close to record lows.

Finally, the determination on the part of state and local authorities to put affordability above housing supply as their primary goal has largely prevented the increase in new housing units that is so desperately needed and would lower housing costs.

Staff Contact: Nicole Wasylkiw

This economic outlook report is adapted from the special report presented to the CalChamber Board of Directors by Christopher Thornberg, Ph.D., founding partner of Beacon Economics.