This Time Is Different

When conducting monetary policy, the Federal Reserve has two goals: keep inflation low and stable, and ensure maximum employment.

For most of last year, inflation was consistently above its target rate of 2.0%. But they believed they were far from meeting the goal of maximum employment, so they kept short-term interest rates low until they could meet that objective.

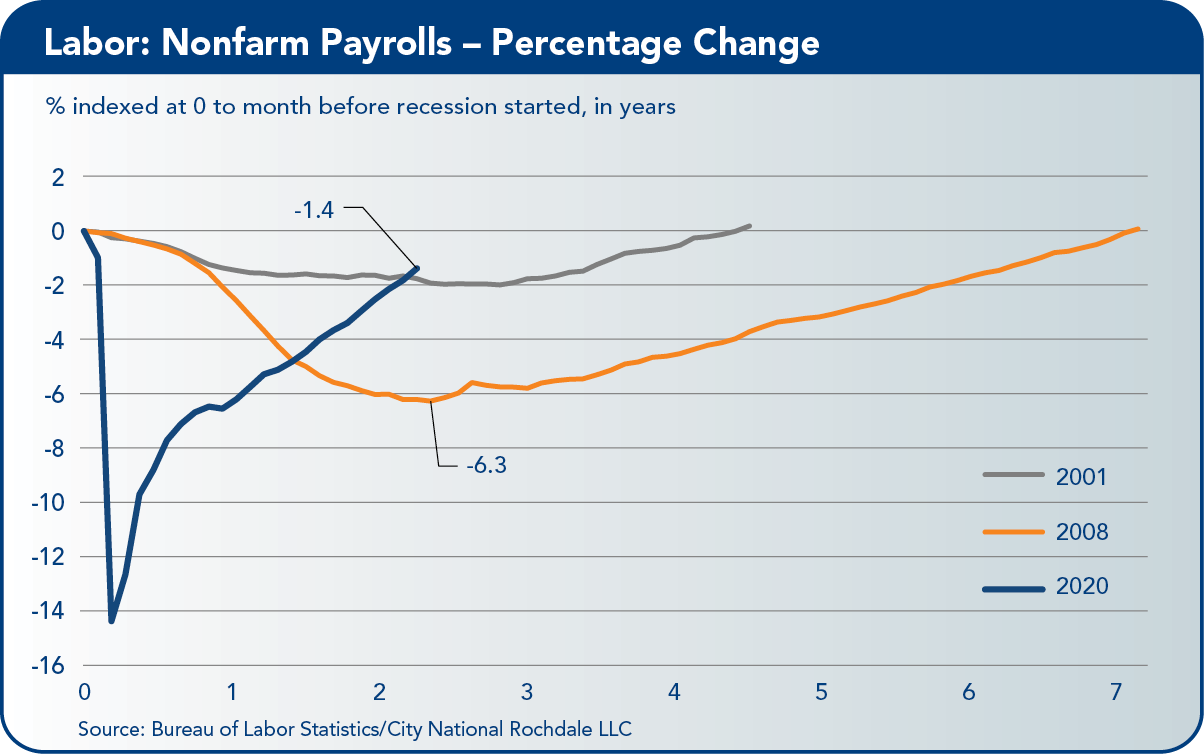

They had good reason for believing that, as payrolls were well below the level before the pandemic. Even today, payrolls stand 2.9 million below that level and are 7.1 million below the trend growth rate.

But now, the Fed believes the economy is close to maximum employment. They are realizing the number of people who want to work is a lot less than before the pandemic. One significant cohort, the baby boomers, has seen a large number of people retiring earlier than past years; they will probably not come back into the workforce, no matter how strong it is.

So with the Fed now believing they have met their two goals, they can begin to increase interest rates from the near-zero emergency level that has been in place since the early stages of the pandemic. Back in December, they made a hawkish pivot with a projection of three hikes in 2022. Since then, several Fed policy makers have been making more hawkish statements that has the market believing even more hikes may happen this year. The federal funds futures market now expects at least six hikes by year end.

The pace of Fed hikes will probably be swift. Unlike most economic recoveries from recessions, the Fed is dealing with a rip-roaring economy this time. Gross domestic product (GDP) growth is faster than anything the Fed has seen in at least the last 50 years, when five recoveries have since taken place. Job growth is also more rapid, and inflation has been much more robust.

Tighter monetary policy is not just a U.S. issue. Markets are expecting higher policy rates from most of the G10 central banks. Most of those banks have already announced plans to end their bond-buying program or are scheduled to do so in the next few weeks. The only central bank that will probably not budge is Japan; they don’t need to. In the past year, GDP growth has been just 1.2%, and inflation has been a paltry 0.8% for the same period.

The Peoples Bank of China (PBoC) is expected to ease monetary policy in the coming quarters. Although GDP growth has been 4.0% in the past year, China is focused on its theme of “common prosperity,” which refers to the government’s aim to generate moderate wealth for all — lower interest rates will help. This is in response to the widening rich/poor gap that has emerged. Also, China is dealing with the repercussions of having a vaccine that is not as effective as the ones used in the West (causing cities to lock down), and it is an election year.

GDP

Fourth quarter GDP rose an impressive 6.9%, with most of the growth coming from inventory accumulation. For all of 2021, GDP grew 5.7%, the fastest full-year clip since 1984.

Of the 6.9% growth, 4.9 percentage points can be attributed to increases in inventories (inventories are part of investment). There was a high level of inventory accumulation due to the year-end increase in omicron that caused an abrupt dip in consumer spending. Inventory swings are always a wildcard and they are notoriously difficult to forecast. Over time, they tend to be flat in a normal business cycle. But these are not normal times, and they have fallen significantly due to strong consumer demand and supply chain complications.

`Consumption growth was up 3.3%, more robust than Q2’s 2.0%. Almost all that growth happened in October. It is nowhere near the stratospheric levels of growth of Q1 and Q2, which were high due to stimulus checks being sent to most households at the beginning of each quarter. Consumption growth, which has been robust this expansion, will soon return to a more sustainable pace due to the lack of receiving future stimulus payments. That said, spending habits are shifting away from goods toward services, specifically health care, recreation, and transportation. This should help put some downward pressure on inflation.

We continue to expect 2022 growth of 3.5% to 4.5%, well above the long-term average of 3.25%. But Q1 data may not be as strong as previously expected since inventory growth was pulled forward into Q4 of 2021. Also, depending upon the omicron trajectory, it may suppress consumption in the early part of Q1. But like last year, we expect to see a strong rebound in spending due to high levels of household wealth and reopening of the economy

Labor

Labor

Payrolls have been growing at a brisk pace in the past year; monthly increases are averaging about 550,000. That is about three times faster than the average of the past expansion. The unemployment rate stands at 4.0%.

In terms of recent data, omicron is causing an impact. There were 3.6 million people absent from work in January. In January 2020, before the pandemic, there were just 1.1 million workers out sick. Also, the labor force increased by 1.4 million, pushing the labor force participation rate up to 62.2. Average hourly earnings surged 0.7%. As a result, wage growth is now up 5.7% year-over-year, a big increase from last month’s yearly change of 4.9%. The amount of job opening continues to be above the number of those looking for a job, which puts upward pressure on wages.

Inflation

Inflation

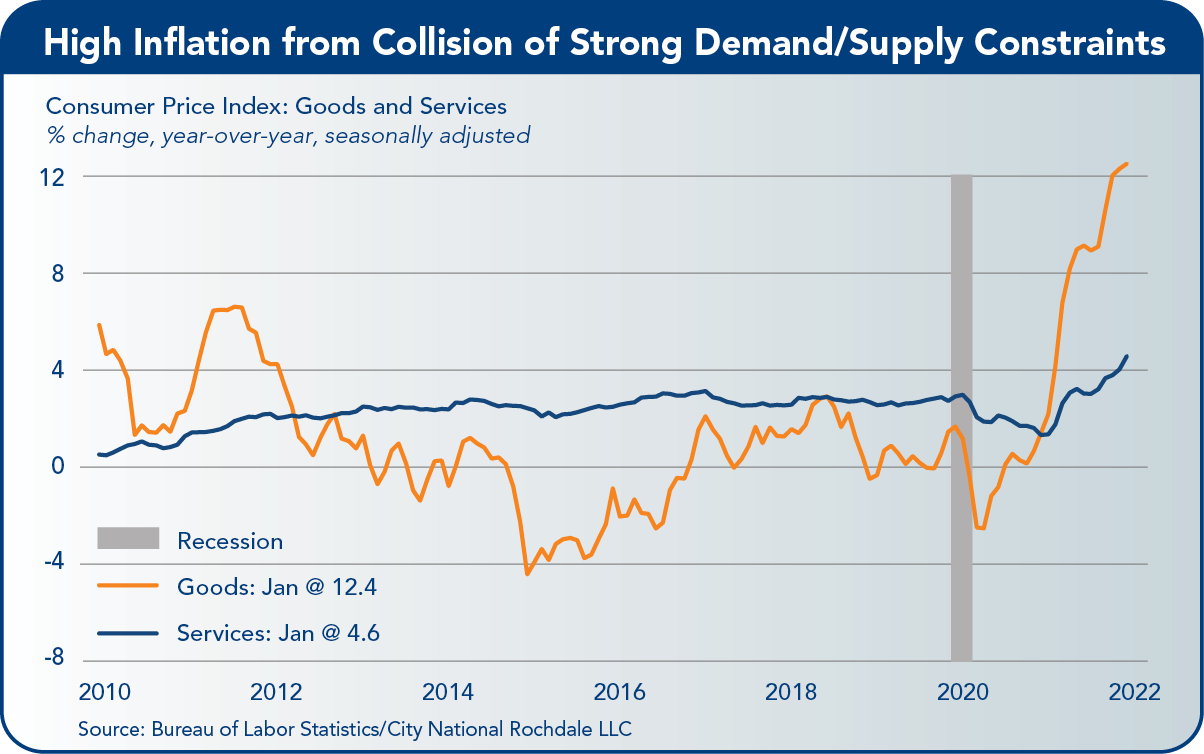

One year ago, the consumer price index was at 1.3% year-over-year; now it is at 7.5%. Last year at this time, the Fed had no plans to raise the federal funds rate in 2022 or 2023 because they expected inflation would remain low, and the economy wouldn’t be near maximum employment. A year ago, the Bloomberg economic forecast for 2022 year end consumer price index (CPI) was 2.1%. How times change.

Inflation began to pick up in spring 2021; much of it resulted from the “base effect” (a jump in prices from a meager value a year earlier). Due to the lifestyle changes from the pandemic, consumers’ purchasing habits skewed away from service toward goods, which put added price pressure on products that quickly became short in supply.

As the summer came along, the delta variant picked up, and supply chain issues got worse. Then in the autumn, price pressures started to widen beyond supply chain sectors, and the Fed began to worry.

There are two types of inflation, and they are both in play:

• First, demand-pull inflation, which puts upward pressure on prices due to increased demand and shortage; it is fueled by low interest rates, increased money supply/household cash, and higher wages.

•Then there is cost-push inflation, which is upward pressure on prices due to increased cost of wages and materials, which is being affected by higher wages, low inventories, and supply chain uncertainties and costs.

The Fed has given up on the idea that inflation will recede on its own. They have come to grips with the difficult task of reining in inflation by raising short-term interest rates and reducing the size of their bond holdings. Both will happen over the next year or two.

Pressure on the Fed continues to mount as the yearly change in inflation continues to rise. The Fed has historically played it conservatively in the early stage of a rate hike cycle.

Although there is a great deal of press about the Fed needing to raise the interest rate by 50 basis points (bps), this is not our view. The Fed is not in the position to shock-and-awe the markets, which causes unneeded volatility.

Their job is to be methodical and tactical. Their goal is the long-term growth of the economy.

If they believe more tightening is needed, a more attractive option is to be even-keeled about it. Maybe raise the funds rate 25 bps at the March, May and June meetings.

If inflation has not started to wane, they still have four more meetings this year to raise the rates and be aggressive in reducing the size of their bond portfolio.

The Fed’s portfolio is nearly $9 trillion in size, more significant than the peak following the global financial crisis, in absolute terms ($4.5 trillion bigger) and relative terms (now at 38.2% of GDP; the previous peak was 25.5%). The large portfolio was an effective tool in bringing down longer-term interest rates, but that stimulus is no longer needed.

Unlike last time, when the Fed maintained the balance sheet near the peak level for 2.5 years, this time, they plan to start reducing it quickly. Last time around, they needed to keep the balance high to provide stimulus; the economy wasn’t nearly as strong as it is today (back then, CPI averaged 1.1%, and the unemployment rate averaged 5.0%).

This time, once the plan is announced, it will be more or less on autopilot. That said, the Fed is expected to engineer a reduction of about $3 trillion by the end of 2023 or early 2024. That amount is needed to bring it to an appropriate level of reserves.

The Fed will debate the strategy of the reduction over the next few meetings. An announcement of the plan is expected this summer.

This economic outlook report to the CalChamber Board of Directors was prepared by Paul Single, managing director, senior economist, senior portfolio manager, City National Rochdale.