U.S. Outlook

Better Than Expected, But Not as Good as It Looks

The stock market sell-off that began at the end of 2018, combined with certain weaker-than-normal economic data, has caused the usual set of perma-bears to predict, yet again, the end of the current U.S. economic expansion.

Beacon Economics is not inclined to agree. We simply do not see imbalances that could cause the kinds of rapid shifts in the economy that would precipitate a recession. With first quarter GDP growth coming in at a solid 3.2% pace along with a number of other positive data trends in recent weeks, it is fair to say that reports of the expansion ending have been, to paraphrase Mark Twain, greatly exaggerated. As for the stock market, it has already bounced back from its early year swoon to new record highs.

The United States is on the edge of its longest expansion ever—and there is no reason to see an end until beyond 2020. While this is good news for the nation, we also shouldn’t expect growth to reach the same pace as in 2018. Rather, the nation’s economic growth will slow to a 2% to 2.5% real pace.

The start of 2019 supports this moderate view. As good as the growth rate in the first quarter (3.2%) was on the surface (it was the third fastest quarter for growth since the start of the Trump administration), half of the growth came from highly transitional sources, namely a big drop in imports and a buildup in business inventories. Growth in final demand in the first quarter was a very weak (1.5%), the worst showing since the start of the administration.

Concerns

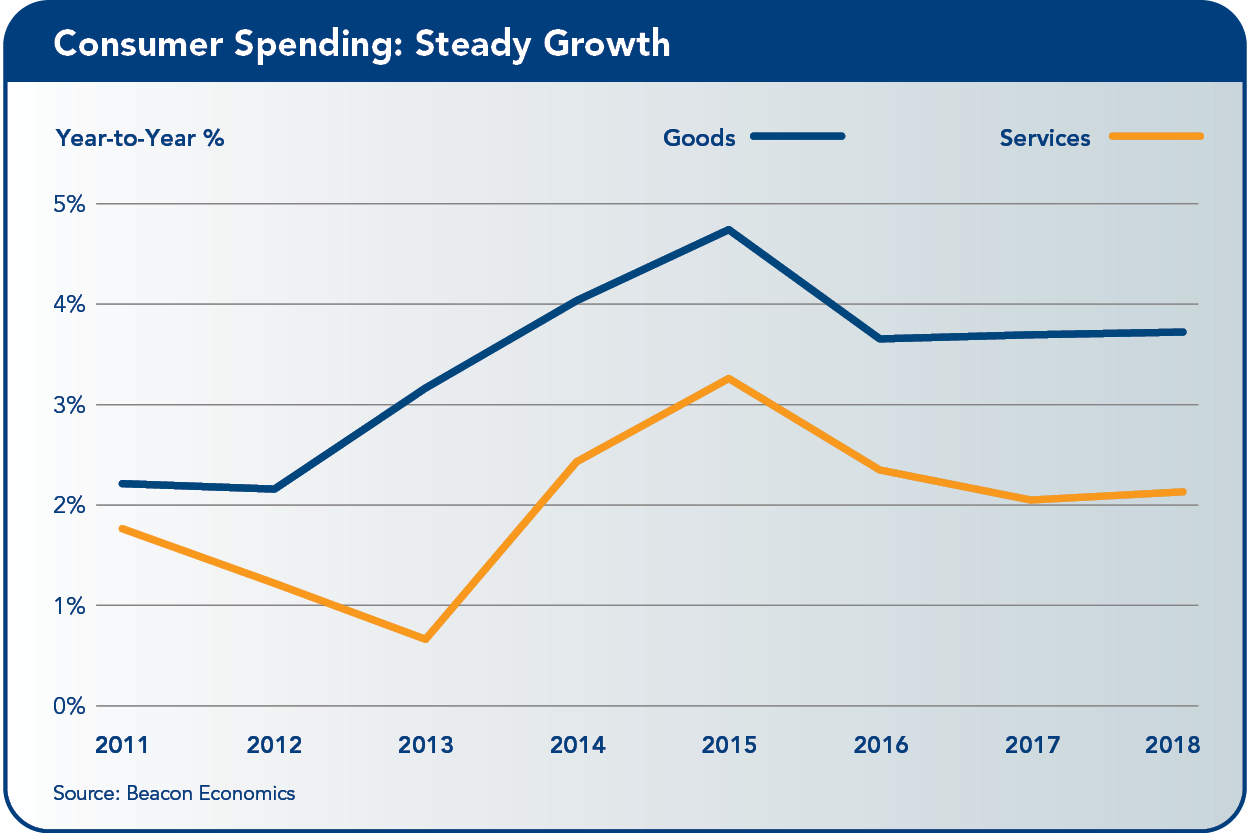

One big portion of the weakness has been from consumer spending. While many economists dismissed the dismal December spending numbers as a fluke generated by the government shutdown, the weak numbers in January and February hardly inspired confidence that the 800-pound gorilla of the U.S. economy was going to maintain momentum into 2019.

But the March numbers then recorded a jump that was one of the largest in the last decade. Perhaps more significantly, personal income for the first quarter also showed an increase in the personal savings rate, so the slow growth in spending was not being generated by income issues. With the U.S. unemployment rate at a 50-year low of 3.6% and wage growth accelerating, expect solid spending numbers for the balance of 2019.

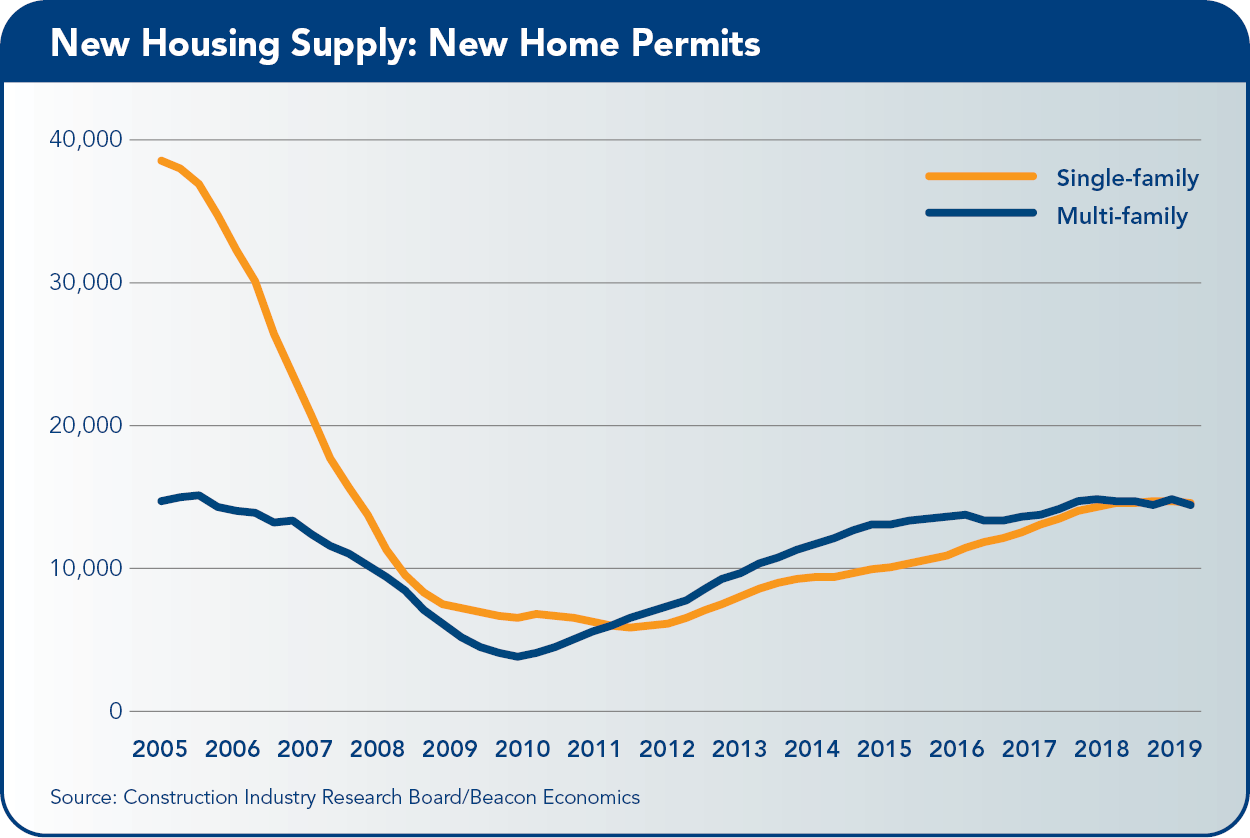

Residential real estate was another area of concern at the end of 2018, and overall, the sector has been a modest drag on the economy for more than a year now, including in the first quarter of 2019. Weak existing home sales and construction trends are the result of rising interest rates, slow population growth, and reduced consumer confidence.

But the fundamentals of the market are solid. Outstanding mortgage debt has grown slowly, and restrictions on bank lending have kept the median credit score for a mortgage borrower above 750 for a full decade. The weak pace of building has also left the United States with one of the tightest housing markets in decades.

In short, this modest swoon was never going to turn into a rout. And in good news for 2019, falling mortgage rates are likely to give the market a boost in the second half of the year. The February and March existing home sales numbers already show signs of new momentum.

Business Investment

Lastly, business fixed investment also started the year with a sharp slowing after solid growth in 2018. Here again, the federal government shutdown, rising interest rates, and lower business confidence can all be counted as sources of the slowdown. But as with consumers and housing, the fundamentals point to better numbers during the balance of 2019. Last year saw solid increases in both corporate and proprietors’ gross profits for the first time since 2014, and capacity utilization is running at a healthy 80%. Combined with labor shortages, expect capital expenditure figures to be solid again this year.

In Beacon Economics’ analysis, business investment is driven by gross profits rather than net profits. We note this because it is too easy to assign the increase in capital expenditures last year to changes in tax rates from the late 2017 tax stimulus plan that caused net profits for corporate America to surge at almost twice the pace of gross profits.

In other words, had the tax plan not been passed, it’s likely we still would have seen most of the increase in business investment in the United States. Beacon Economics believes that the tax plan had a greater effect on U.S. economic growth through increased government and consumer spending—a boost that will not continue into 2019.

Counterweight

And, of course, there is a counterweight on the otherwise good fundamentals the U.S. economy is currently enjoying. In 2018, the federal government borrowed more than $1 trillion to cover the gap between revenues and expenses, twice the pace of 2017 borrowing and the worst showing since 2012 when the nation was still clawing its way out of the “Great Recession.”

With rapid growth in entitlement programs due to the retirement of the boomer generation, it seems likely that the deficit will only get worse in years to come. While a public debt crisis is still far in the future, such misguided policies are bringing the day of reckoning that much closer.

California Outlook

No Surprises Here

California defied naysayers by putting in another solid economic performance in 2018, but has gotten off to a slower start in 2019.

This is not indicative of a pending recession, but rather the result of long brewing problems with labor force growth and rising housing costs, both of which require time to solve.

In the meantime, California will continue to grow, led at the regional level by the tech sector-fueled San Francisco Bay Area economies.

Slow Growth Ahead

Moving through the first half of 2019, the state has shifted to a lower pace of job growth compared to recent years. California added jobs at a 1.4% yearly clip in March, with growth occurring across nearly all of the state’s regions. Through the first three months of the year, job gains fell short of last year, averaging 1.4% this year compared to 2.5% in 2018.

But last year’s gains were boosted temporarily by enactment of federal tax cuts early in the year, the effects of which will fade this year and next. Trade-related sectors also surged last year ahead of anticipated trade restrictions, but have gotten off to a slow start this year because of the continued uncertain outlook in that sector.

But last year’s gains were boosted temporarily by enactment of federal tax cuts early in the year, the effects of which will fade this year and next. Trade-related sectors also surged last year ahead of anticipated trade restrictions, but have gotten off to a slow start this year because of the continued uncertain outlook in that sector.

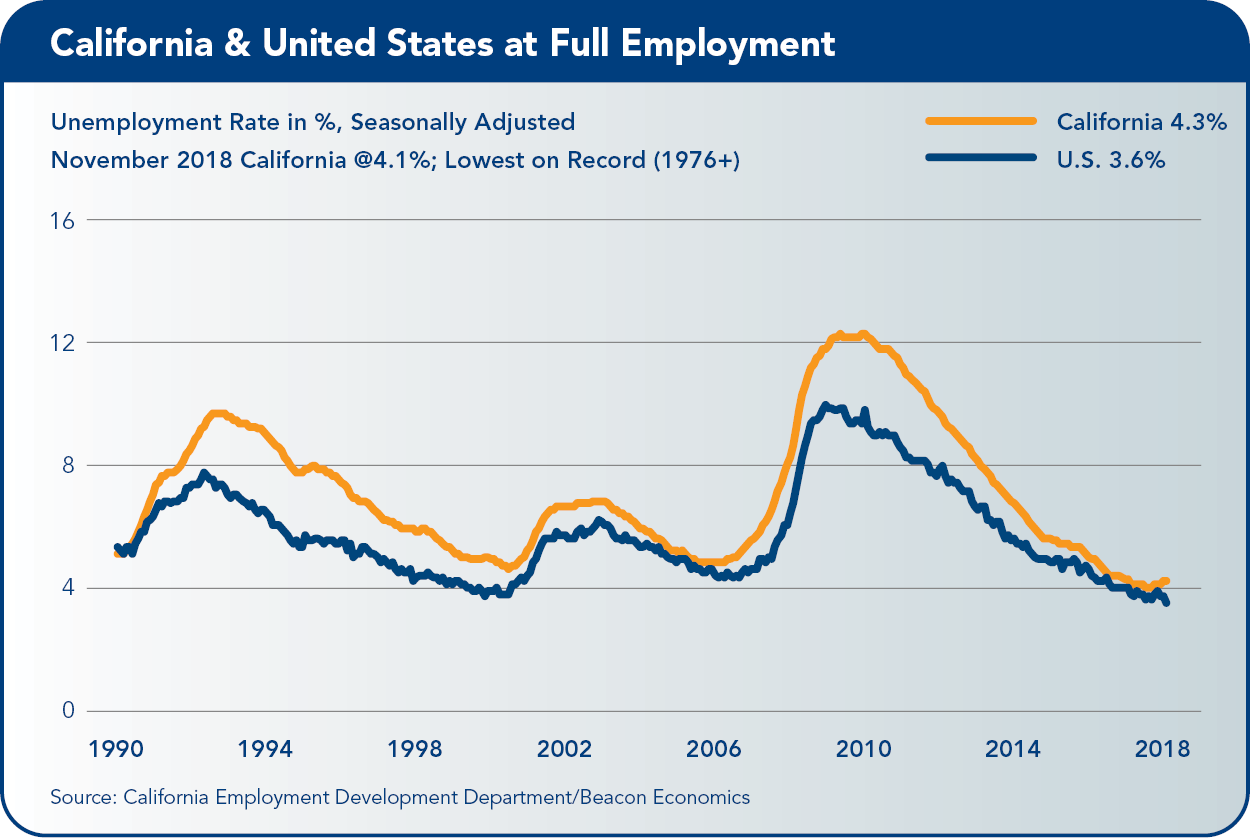

California’s unemployment rate continues to move sideways, at or near its record low, with the March rate at 4.3%, unchanged from one year earlier. Evidently, labor force growth is just enough to keep the unemployment rate on a steady course, but at the same time it is holding back industry job growth.

California added 238,500 jobs in March compared to one year earlier, with gains occurring across nearly all of the state’s industries. Health Care led the way with 56,100 jobs added, followed by Professional, Scientific and Technical Services (+42,100 jobs), and Leisure and Hospitality (+34,100 jobs). Government, Construction, and Administrative Services each added approximately 24,000 jobs over the year.

In percentage terms, Professional, Scientific, and Technical Services outpaced all other industries with a 3.3% gain, followed by Mining and Logging (+3.1%), Construction (+2.9%), and Transportation, Warehousing, and Utilities (+2.5%). Retail Trade, Wholesale Trade, and Finance and Insurance all recorded job losses totaling 17,800, equivalent to 0.1% of the state’s 17.4 million jobs.

Virtually every region of the state added jobs in March, led by San Francisco (metropolitan division – MD), with a 3.8% year-to-year gain, equivalent to an impressive 42,600 new jobs. Fresno County (+3.7%), Sacramento (metropolitan statistical area – MSA) (+2.8%), and San Jose (MSA) (+2.5%) followed in terms of percentage gains.

Although much larger in terms of jobs and population, the regions of Southern California experienced relatively small gains, both in percentage and in absolute terms.

Differences in regional labor force growth are dictating job gains around the state at this time. Statewide, the labor force has grown by an average of 1.5%, year-to-year, so far in 2019.

Regionally, Fresno, San Francisco, Santa Clara, and Sacramento counties have all seen their labor forces grow by more than 2% this year, while labor force growth in Los Angeles and Orange counties has been negligible, and San Diego County and even the recently high-flying Inland Empire come in at just shy of 1%. In brief, where labor force growth is present, regional economies are able to grow jobs and expand.

To be sure, California continues on an impressive growth path despite the slowdown in job growth. Gross State Product advanced by a 3.5% rate last year, faster than the nation and among the fastest growing states. California workers have experienced consistent, if subdued, wage gains—up 4.5% over the first three quarters of 2018—not unlike the country as a whole. And it routinely leads other states by a wide margin in terms of the share it captures each year.

Ultimately, the current slowdown in job growth is no surprise. It has been “baked in the cake” for some time, a consequence of slow labor force growth and the state’s high cost of living. But a slowdown does not equal a contraction. There is every expectation that California will grow through the balance of 2019 and into 2020, riding the wave of the nation’s record-setting expansion.

Housing Market Potential

Despite California’s housing market struggles in 2018, there is potential for this year to be better than many expect. Statewide quarterly home sales declined last year as rate increases and higher prices drove affordability down. This pattern continued into the first quarter of 2019, the hangover effect from late 2018, a period when high mortgage rates had a chilling effect on open escrows that ultimately were recorded as closed sales (escrows) in early 2019.

Having hit nearly 5% in November 2018, the 30-year fixed rate has declined in recent weeks to just over 4%. Lower rates over the 2019 busy season should help boost demand. Moreover, softer prices are expected this year as a result of an increase in the supply of homes for sale over the last few months.

Having hit nearly 5% in November 2018, the 30-year fixed rate has declined in recent weeks to just over 4%. Lower rates over the 2019 busy season should help boost demand. Moreover, softer prices are expected this year as a result of an increase in the supply of homes for sale over the last few months.

Taken together, it should not be a surprise to see sales improve in the second and third quarters of this year while the statewide median price will advance modestly.

Near-term concerns about the housing market should not distract us from the long-run challenge the state faces in terms of its housing shortfall. Just released population estimates by the California Department of Finance paint a picture of slower population gains, both statewide and in many regions.

California’s population grew by just 0.5% from 2018 to 2019, with high cost areas like San Francisco, Santa Clara, and Orange counties growing by less than the state. Los Angeles County (California’s largest) registered a marginal population decrease compared to last year.

Slow population growth in California has occurred because of both slow natural increase and weak net migration. It doesn’t take much to connect the dots between the state’s high housing costs and the slow growth of its population and labor force.

Conclusion

California continues to exhibit a dynamism that is found in just a handful of other places around the country and the world. It is the fifth largest economy on the planet, a global center for both the world of technology and the creative economy, and the primary destination for venture capital. One can only imagine how much growth might be unleashed if the state can successfully address its housing challenges.

The California Chamber of Commerce Economic Advisory Council, made up of leading economists from the private and public sectors, presents a report each quarter to the CalChamber Board of Directors. The council chair is Christopher Thornberg, Ph.D., founding partner of Beacon Economics, LLC. The report was presented to the CalChamber Board by Robert Kleinhenz, director of economic research at Beacon Economics.