California Outlook

Long-Run Challenges During Times of Economic Gain

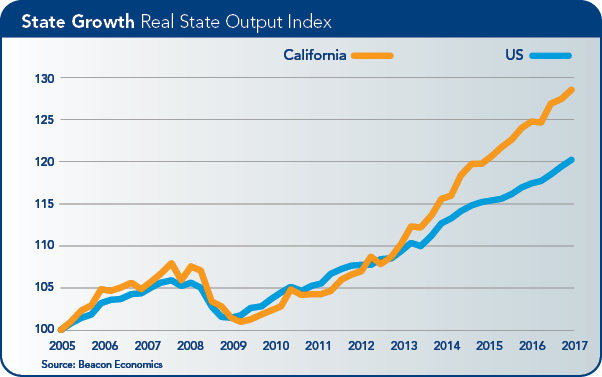

The U.S. economy has experienced steady growth in recent years, and later this year, the current economic expansion will become the second longest on record. Throughout much of this expansion, California has outpaced the nation and many states in terms of economic growth and job gains, and improvements in its unemployment rate, fueled by strength in many of its key industries.

California will continue to lead the United States in 2018, making this year an opportune time to take on both current and long-term challenges.

California began 2018 on a high note with January employment numbers showing the largest yearly job gain (2.4% or 400,000 jobs) in 18 months. In March, the state added jobs at a steady 1.9% year-to-year pace, led by health care, construction, leisure and hospitality and professional, scientific, and technical services, accounting for two-thirds of this increase.

In percentage terms, the state was led by natural resources and construction, education services, health care, and logistics, largely continuing a pattern of industry gains that has prevailed over much of the past year.

Outpacing U.S.

January’s gains come on the heels of six consecutive years during which California outpaced the nation in percentage job gains. Moreover, updated job numbers released in March revealed that California’s job gains were better than initially reported, up from an initial estimate of 1.8% growth to 2%, because of substantial upward revisions in important industries such as health care, as well as professional, scientific and technical services, and logistics.

The broader state economy displayed continued momentum, with annual taxable sales showing a 4.9% gain over 2017, and gross state product rising by 2.3% year-to-year in the third quarter of 2017. Fueling these advances, personal income increased by 3.8%, the third highest growth rate among the 50 states.

Meanwhile, per capita personal income in California stood at $58,500/year in the third quarter of 2017, 16% higher than in the United States as a whole. But while California saw a 3.1% increase in personal income, far outpacing the 1.9% gain nationally, gains in purchasing power have been tempered by inflation running at nearly 3% in the state compared to just 2% nationally.

Unemployment Rate

With California hitting its lowest unemployment rate since 1976, wage gains in the state have accelerated in recent years. Average weekly wages in California increased by 4.3% in 2017, the largest increase in the last 10 years.

With limited increases in the labor force expected this year, workers are almost guaranteed to see wages rise again. And it is too soon to gauge the effects of the hike in the statewide minimum wage as pay hikes are currently being driven by the scarcity of labor more than anything else.

Steady job growth and limited increases in the labor force will keep the unemployment rate low and push up wages for nearly all workers. With these gains in financial and economic well-being, households in California will fuel growth in their local economies by buying homes, appliances, and cars, and causing expansion in local serving industries, such as retail stores, restaurants, and personal services.

Meanwhile, the state’s logistics, technology, and other external-facing industries will benefit from growth domestically and among our trading partners.

All in all, California’s economic outlook through the next several quarters is good, in fact, somewhat better than was previously expected, making this an ideal time to devote serious attention to the state’s long-run concerns.

Housing

Long-Term Challenges… Short-Term Opportunities

In looking at California’s long-term challenges, the housing problem must be near the top of the list because of its significance for so many of the state’s residents and its economy.

While Californians clearly understand that high home prices limit affordability, the obvious solution seems less clear: High prices reflect scarcity that can be addressed only through increases in supply.

California’s median home price was $464,000 in the fourth quarter of 2017, nearly double that of the United States, where the median price stood at just over $250,000. Since 1990, California’s median home price has routinely been significantly higher than that of the nation.

Home prices in inland California are closer to the U.S. norm: $252,000 in Fresno, $340,000 in the Inland Empire, and $380,000 in Sacramento. However, the situation is quite extreme in coastal areas, with the median price in San Francisco at $1.3 million, $605,000 in Los Angeles County, and $596,000 in San Diego County.

Renters are also challenged by the high cost of housing. The number and share of renting households in the state of California grew in the years following the Great Recession. With a limited response on the supply side, average rents rose steadily in many areas of the state.

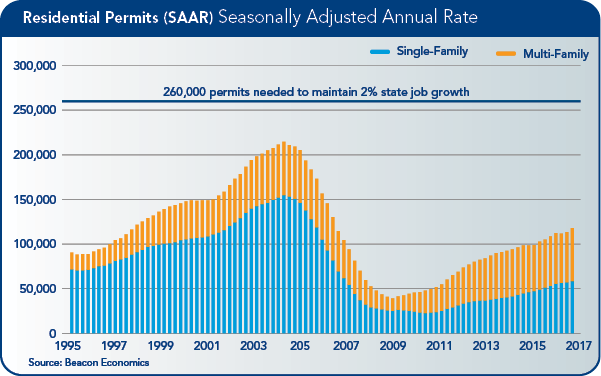

The magnitude of California’s housing shortage is well documented. At present, the state is estimated to need about 200,000 new housing units built per year, yet it has barely seen more than 100,000 units come on line in each of the last few years. As implied above, the state needs a mix of both single-family and multifamily housing, as well as a mix of for-sale and rental housing.

Regional Housing

To be sure, the state and its regions periodically estimate housing needs and set housing goals. In fact, state law requires that metro areas and their jurisdictions develop multi-year housing goals known as the Regional Housing Needs Allocation (RHNA). Few jurisdictions come close to meeting the RHNA-based housing goals, however, because there is little incentive to do so.

In the calculus of local government finance, a new housing unit will impose new burdens on government services, yet yield only a modest increase in property tax that is mostly controlled by state government. Local governments are far more inclined to prefer retail development, which has the potential to generate new taxable sales that go straight into the general fund.

Recognizing that the state has a chronic housing shortage and understanding that inadequate housing has the potential to impede economic growth, state legislators have succeeded in passing legislation that has the potential to make a difference. Laws such as SB 35 (Wiener; D-San Francisco; Chapter 366) put teeth behind the RHNA goals, stipulating that a given project which complies with local land use regulations may receive ministerial approval if the jurisdiction in which it is located has not met its housing goals.

SB 35 has lent new urgency to a problem that has festered for many years, and very likely will force local jurisdictions to rethink their housing strategy.

In response, local jurisdictions must first acknowledge that population growth is an inevitable part of their future. They must take steps to understand what that growth will look like, plan adequately, and, finally, execute those plans.

This effort must address the concerns of both current and future residents: renters as well as homeowners, apartment dwellers as well as occupants of single-family homes. Doing so will go a long way toward addressing the state’s housing needs while also ensuring its long-run economic dynamism and vitality.

The California Chamber of Commerce Economic Advisory Council, made up of leading economists from the private and public sectors, presents a report each quarter to the CalChamber Board of Directors. This report was prepared by council chair Christopher Thornberg, Ph.D., founding partner of Beacon Economics, LLC.

The California Chamber of Commerce Economic Advisory Council, made up of leading economists from the private and public sectors, presents a report each quarter to the CalChamber Board of Directors. This report was prepared by council chair Christopher Thornberg, Ph.D., founding partner of Beacon Economics, LLC.