It’s a timeworn California cliché: an earthquake splits the state from the rest of the country—freeing us from the hidebound thinking of Old America.

It’s a timeworn California cliché: an earthquake splits the state from the rest of the country—freeing us from the hidebound thinking of Old America.

Well, reboot that cliché. An earthquake has sundered California, but it is splitting the state from itself.

From a distance it seems the California economy couldn’t do any better. Our gross domestic product (GDP) is in the top six among nations. We lead states in economic output per capita and statewide employment growth is the envy of the nation. We’re creating wealth faster than any time since the Incan conquest.

But behind those marquee numbers lurks a complicated mix of prosperous and desperate. Considering the cost of living, our poverty rate is highest in the nation. According to the Public Policy Institute of California, more than one in five families lived in poverty in 2013 and 9% of families lived in deep poverty.

Nearly one of three Californians receives subsidized health care through Medi-Cal. More than 3.3 million schoolchildren receive subsidized school lunches—about half of total public school enrollment.

California has the highest percentage of people living in poverty. Even among huge wealth generation and employment gains, millions of California families cannot reach the California dream.

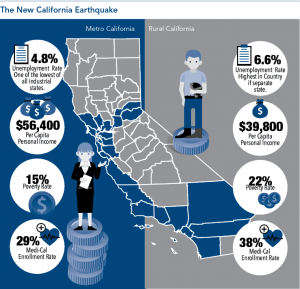

The new California earthquake has a clear geographical dimension. Grab the 36 counties in rural, mountain and Northern California, and the aggregate unemployment rate is 6.6%. If rural California were a separate state, its unemployment rate would be the highest in the country.

On the other hand, unemployment in the 22 coastal and metropolitan California counties is just 4.8%, one of the lowest of all industrial states.

Rural California also suffers more widespread poverty than its coastal and metro neighbors. The official poverty rate is higher, as is enrollment in Medi-Cal, the state’s health care program for poor residents.

Poverty is not limited to rural and inland California. Much of the poverty in coastal California is a function of housing costs that distort expenses of wage earners. Zillow reports that renters in the Los Angeles metropolis pay 48% of their monthly income for the median rent. Almost half of working-age adults in Los Angeles County double up with one another in housing units. According to analysis by the Milken Institute, median rentals of one-bedroom apartments exceed 30% of median income in the San Francisco Bay Area, Los Angeles and San Diego.

Even when employees can find affordable housing away from the metropolis, the long and slow commute adds yet another financial burden and social stress.

The surest path to economic success is a good education. But here again the California fault lines divide educational attainment.

According to the Milken Institute, a region’s per capita economic output is closely tied to its educational attainment. And in what cannot be a surprise, the regions with the third- and eighth-ranked educational attainment nationally are in the San Francisco Bay Area, and notably have the first- and third-ranked GDP per capita.

Just 80 miles inland, five regions in the San Joaquin Valley are in the bottom 10 of educational attainment (among the 150 U.S. metropolitan areas), and also scrape the bottom in per capita GDP.

For Californians 25 years of age and over who do not possess four-year college degrees, 469,800 residents left the state mainly because they could no longer afford to live here. On the other hand, California was a net importer of 52,700 residents with a bachelor’s degree or higher.

California’s research universities are magnets for top students and global companies that hire them. It is no coincidence that the regions of California with the lowest unemployment and highest economic success are those that are home to our research universities.

Certainly, not everyone can achieve a four-year higher education degree, but we should expand opportunities and enhance workforce training to higher-skilled, well-paid careers that don’t require a four-year degree.

Still, economic success breeds its own problems, even in Metro California. A high cost of living is driven in large part by housing shortages and long commutes, which in turn can be addressed only through an increased housing supply and more infrastructure investment.

Expanding Opportunity

Increasing opportunity and offering everyone a slice of the pie is within reach of the state leaders. Lawmakers should start with these five goals:

1. Invest in Transportation and Water Infrastructure.

2. Increase Housing Supply.

3. Make Energy More Affordable.

4. Update Labor Laws and Reduce Litigation.

5. Invest in Education and a Skilled Workforce.

California is a wealthy state with great natural and intellectual resources. It is within the power of state leaders to foster growth and increase opportunity—not merely to defend what some have already achieved.

This is an excerpt of the overview essay from the California Chamber of Commerce 2017 Business Issues and Legislative Guide. Read more at www.calchamber.com/businessissues.