U.S. Outlook

Looking back, 2018 was clearly a solid year for the U.S. economy, with vastly more positives than negatives to reflect on. The nation’s economy grew by 2.9% in real terms over the year, a modest uptick from 2017 and 2016, and the best number since 2015. Acceleration in growth occurred almost across the board, but the greatest contributions came from government and business investment. Exports had a good year despite ongoing trade disputes with key partners.

Labor markets also added plenty of jobs last year — and will likely continue to do so in 2019. The job openings rate at the end of the year was 4.7%, significantly higher than the unemployment rate. Household finances look good as well. The consumer savings rate ended the year above 6%, even as the financial obligation ratio (the share of disposable income used for debt and rent payments) fell to a record low. Wages are rising, consumer spending is solid, and with the exception of autos, the debt markets look very clean.

Still, public sentiment has turned remarkably grim as we move further into 2019 and there have been a surprising number of predictions calling for a potential recession in the next two years.

Drivers of this pessimism range from the stock market plunge and slow pace of sales in the housing market to fears surrounding the impact of an expanding trade war with China and decelerating global growth. A smattering of recent economic data seems to support such fears, from a dismal showing for retail sales in December to weak employment growth in February.

Unfounded Concerns

Despite all the negative sentiment, Beacon Economics sees little reason (still) to change our near-term outlook for the U.S. economy. Most of the current concerns are unfounded in our view.

China is offsetting U.S. tariffs by depreciating the yuan. The slowing of U.S. exports to China has been made up elsewhere. Corporate fundamentals, including profits and employment, look better now than two years ago. And this stock market decline is the sixth major selloff since the Great Recession came to an end — an unprecedented level of volatility that is more a sign of problems in the stock market, not the economy.

Yes, U.S. economic growth will slow from its pace in 2018, falling to the low 2% range, but this is only because the sugar rush created by the fiscal stimulus tax plan of 2017 is wearing off — as easily anticipated.

And while there have been some weaker-than-normal numbers in certain economic data, these seem to be in line with the normal ebb and flow of economic growth rather than any bellwether of an impending downturn. The difference is best illustrated by the current handwringing over the nation’s residential real estate market (the focal point of this quarter’s national outlook).

Eventually, the current economic expansion the United States is experiencing will come to an end. When it does, that ending will be driven by a large, negative shock to the economy, which in turn will be driven by some major internal imbalance that has formed.

To date, Beacon Economics has yet to see any imbalance develop within the U.S. economy that has the capacity to cause a downturn, much less a recession, in the near term.

Singing The Housing Blues

Housing has always been an important indicator of the U.S. economy for both macro and individual reasons. It has been a leading indicator of economic growth for the majority of business cycles over the past 70 years and, of course, played an outsized role in the “Great Recession.” For most households, housing is the largest expense, and for homeowners, their largest asset. It’s little wonder that public sentiment suffers when negative news about housing begins to dominate the front page. The grim headlines can best be summed up by the closing line of a recent New York Times article: “In other words: Housing is in recession already.” (February 19, 2019)

Strong words — with little basis in reality. There is little doubt the market is flat, but flat is not a downturn. According to data from the U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis, economic activity in the residential real estate sector has changed very little for two years, either up or down.

When parsing out the components of this data — housing starts, sales, inventories — the same picture emerges. Home prices are still rising, albeit at a slower pace. Housing has shifted to neutral, but it has not moved toward anything resembling a decline.

Reasons for Flat Housing Market

Why has the U.S. housing market been flat? There are three major reasons, short-, medium-, and long-term.

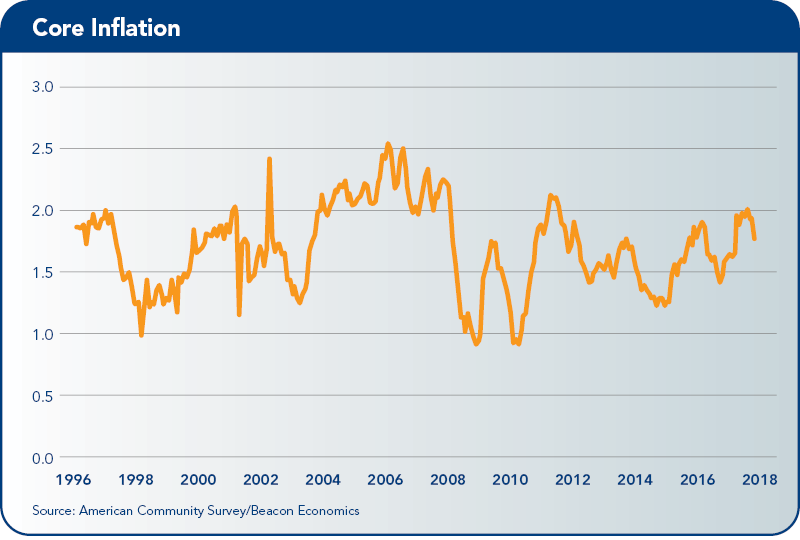

• The short-run driver is interest rates, which have been gradually rising over the last few years. Interest rates are still low from any longer-term perspective, but the market still has to adjust to them. This tends to precipitate a short period of slowing as prices (and thus sales) adapt to new fundamentals.

But while sales of existing homes have slowed, so too has the number of units being put on the market, with the available inventory of homes well below 5 months’ supply nationally. This represents a lower level of supply than in 2014.

The good news is that interest rates have stabilized — and will likely remain in their current range for a while. Inflation is cooling and the Fed has stopped tightening. Beacon Economics expects the negative influence of interest rates on the housing market to fade in the spring.

• In the medium-term, U.S. Census data over the last few years have shown a rapid pace of population movement within the United States from the Northeast and Midwest to urban areas in the South and West. Many of these destinations (with California being the poster child) have constrained housing construction markets due to strict zoning, high fees, slow-growth sentiment, and downright NIMBYism.

As a result of these constraints, there has been a greater utilization of existing housing stock rather than a significant increase in building permits, resulting in tighter inventory and higher prices.

• Lastly, there is the long-term issue of slow growth in the U.S. population base, driven by both low childbirth rates and a sharply decelerating pace of immigration. Overall population growth in the nation is currently running about 2 million per year — substantially slower than 20 years ago when it was over 3 million annually.

Working age population growth has slowed even more dramatically, from over 2 million per year to just 1 million. The United States, as a whole, simply doesn’t need as much new housing as it used to.

Add it all up and the fact that housing starts and sales are flat is hardly a surprise. Still, far too many pundits are trying to link what is happening now to what happened back in 2006 when the great housing bubble began to unwind.

Housing Fundamentals

There is no comparison. The fundamentals of today’s housing market — including affordability, vacancy rates, credit quality, household incomes, and debt levels — look better than they have for 20 years.

This stands in complete contrast to 2006 when each one of these indicators was severely unbalanced. Take for example housing starts, which were running well over 2 million in 2005, vastly more than population growth would indicate was appropriate.

The “slow” 1.2 million unit pace of building in the past few years is in step with population growth or possibly even a little low. But a lack of supply should give you more, not less, confidence in the fundamental strength of the market.

Another example is the pace and quality of mortgage lending. In 2006, mortgage debt was expanding by 15% per year. Today it is less than 5%. And the median credit score of a borrower today is above 750 — compared to below 700 in 2006.

The aggregate housing debt to equity ratio is also better today, and that can be seen in household finances. According to the American Community Survey from the U.S. Census Bureau, in 2017, 27% of households with a mortgage used over 30% of their income on housing costs; in 2016 it was 29% and in 2006, 37%.

The current slowness in the U.S. housing market is not a downturn in any broader sense, nor will it turn into one. On the contrary, all the market worry is much ado about nothing and as 2019 advances, market activity will start to pick up again. This canary in the coal mine will soon wake from its short nap and start singing again.

California Outlook

Now Is the Time to Move Wisely into the Future

California’s economy, in the first part of 2019, remains on a steady growth track despite concerns about how long the current expansion will continue.

Like the nation, the state economy benefited from expansionary fiscal policy in the form of tax cuts coupled with increases in government spending that pushed the labor market closer to full employment and fueled solid job gains.

Tech-related sectors made significant contributions to the state’s economic growth, as did a handful of other industries. Still, California faces a huge housing challenge, something that the new governor is addressing head on.

Staying the Course in California and Its Regions

Despite the turbulence created by the Trump administration’s trade wars, the chaos surrounding Brexit, and a slowdown in the global economy, California saw continued economic growth in 2018 and early 2019.

Through the first three quarters of last year, California’s gross state product grew by 3.5% year-to-date, with nearly all major industries expanding over that period. Significant contributions came from technology, real estate, and manufacturing, while health care, construction, and transportation and warehousing made smaller contributions.

Low Unemployment

The state and many of its metro areas continue to be at or near record lows in terms of unemployment rates, picking up where they left off last year. The statewide rate was 4.2% in January, coasting just a hair above the all-time low of 4.1% for several months running. Indeed, recent increases in California’s labor force have kept the unemployment rate above the 4% threshold.

The state’s labor force growth has been trending up in recent months, increasing by 1.5% in January 2019, up considerably from 0.6% one year earlier.

California added 246,400 jobs in January compared to one year earlier, equivalent to a 1.4% increase. Job gains occurred across nearly all of the state’s industries, led by Health Care with 56,000 jobs added, and followed by Professional, Scientific and Technical Services (+36,400 jobs), Leisure and Hospitality (+33,200 jobs), and Administrative Services (+30,500 jobs).

In percentage terms, Transportation, Warehousing, and Utilities led all industries with a 3.6% yearly increase, followed by Mining and Logging (3.5%), Construction (3.4%), and Professional, Scientific and Technical Services (2.9%). Leisure and Hospitality and Administrative Services both followed with an increase of 2.8%.

Three industries in the state shed jobs in year-to-year terms, for a total of just more than 22,000 positions lost. This includes a loss of 12,600 jobs in Retail Trade, which continues to transform itself in response to the realities of a multi-channel marketplace.

Still, January’s job losses are small relative to California’s 17.3 million wage and salary jobs, accounting for 0.1% of all jobs in the state.

Rising Paychecks

Consistent with an unemployment rate that has been low on a sustained basis, paychecks have been on the rise. Average hourly earnings in California rose 4.8% year-to-year in January 2019, following a 5.5% gain in December. By comparison, hourly wages have risen by just over 4% nationally.

In all, job gains in California continue across a wide array of sectors, including external income-generating industries such as technology, transportation, manufacturing, and tourism, each of which also contribute to the state’s foreign trade picture. These industries have been challenged over the past year by uncertainty surrounding the Trump administration’s trade policies, as well as a strong dollar, and yet, the state’s merchandise exports rose by 3.8% in 2018.

Over the same period, imports were little changed (up 0.1%), fueled by income growth that also has supported increases in local population — serving industries such as health care, education, and food and bar establishments.

In the public sector, Government sector jobs continue to grow in number, with most of the 19,300 positions added in January appearing at the Local Government level. The state added jobs as well, but Federal job counts continue to edge down.

In Sacramento, the state budget is expected to rack up another surplus in fiscal year 2019 as California’s rainy day fund continues to grow.

Looking across the state, every region began the year with increases in wage and salary jobs. In absolute terms and percentage terms, California was led by San Francisco (MD), with a 3.8% year-to-year gain in January 2019, equivalent to 42,600 jobs added. Fresno County (3.2%), Monterey County (2.8%), and Santa Barbara County (2.8%) followed in terms of percentage gains, while large absolute job gains occurred in most Southern California counties, Sacramento, and San Jose.

Housing Requires Both a Sense of Urgency and Patience

Despite sustained growth in the California economy, the housing market struggled in 2018, with weakness carrying into early 2019. Statewide, existing home sales fell by 12.6% from January 2018 to January 2019 while the median home price increased just 2.1% to $539,000, according to the California Association of Realtors.

The sharp drop in sales in January has triggered concern about this year’s housing market outlook, but January’s closed sales figures reflect conditions in the market in November and December when these sales were initiated.

The 30-year fixed mortgage rate hit nearly 5% in mid-November, the highest in years, but has since retreated below 4.5%. Given recent increases in the state’s supply of homes, and assuming rates hold steady in the next few months, the peak season of 2019 could be better than many expect.

Looking beyond the near-term performance of the housing market, California’s newly elected governor, Gavin Newsom, and the state Legislature have focused directly on the state’s chronic housing shortage, a problem that has been growing in magnitude for many years.

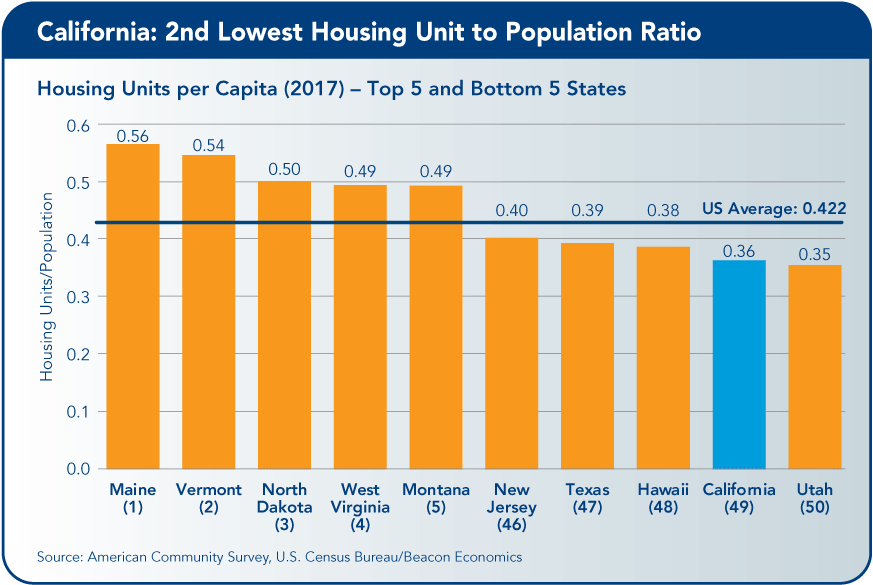

In broad terms, given recent population growth, California should have been building about 200,000 new housing units each year for several years running. However, just 115,000 units were built last year, and even fewer earlier in the decade.

Land Use Decisions Local

At stake is California’s economic future, which is increasingly jeopardized by the high cost of housing. But while Sacramento is searching for solutions to this stubborn problem, it must also face the reality that land use decisions, such as those related to new housing, have historically been under the purview of local officials and local zoning regulations.

According to state law, local jurisdictions are required to plan for their housing needs over time. The so-called Regional Housing Needs Assessment (RHNA) is a framework for establishing housing needs from the state down to the community. But because there are no enforcement mechanisms behind RHNA, jurisdictions can simply pay lip service to their stated RHNA housing goals or ignore them altogether.

Governor Newsom has taken an aggressive approach to the problem thus far, with a carrot and a stick. On the one hand, he would like to offer incentives to cities to build more housing, while on the other hand, he has threatened to withhold transportation funds from those who do not. He also has sued cities for failing to comply with RHNA requirements.

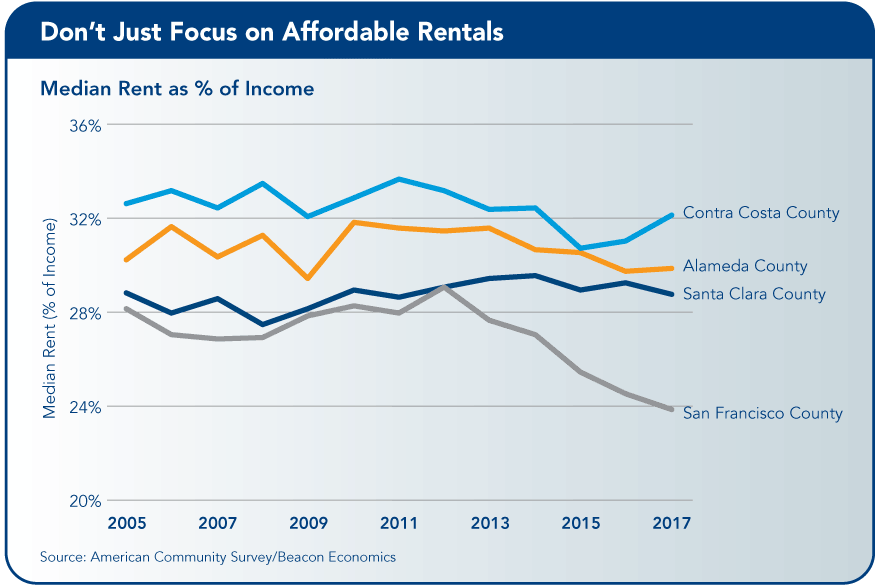

There is no doubt that California needs more housing — more housing of all types: multi-family as well as single-family, affordable as well as market-rate units. And the urgency to deal with this problem has never been greater. Still, there are good reasons to pursue the situation with both a sense of urgency and a heavy dose of patience.

More than ‘Sticks’ in Ground

A truly comprehensive solution to California’s housing problem involves more than just finding vacant sites and putting “sticks” in the ground. Residents have deeply seated and long-held attitudes about their neighborhoods, and very often do not want anyone changing their corner of the world.

At the same time, local jurisdictions and their elected officials find themselves in a quandary. Many local leaders want their cities to grow, but the structure of state and local taxes discourages residential development, which adds little to government coffers but imposes public service costs on local government.

In California, there often are greater fiscal benefits from other land uses that directly or indirectly generate taxable sales and other revenue streams for a city’s general fund. And, at present, building industry constraints pose yet another complication. With California’s economy at full employment, construction labor is expensive and limited in availability, while other construction inputs like lumber and so on are likewise scarce and costly to acquire.

Examine All Dimensions

It has taken a long time to get to where we are now with the state’s housing shortage, and it won’t be solved overnight. State and local officials along with other stakeholders must be willing to examine all the dimensions of the housing problem if they want to craft long-run solutions that work.

This means looking at the tax code, zoning, permitting processes, and even the California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA), while also recognizing that changing residents’ attitudes may be the most difficult nut to crack.

The sooner stakeholders embark on this path — which requires a thoughtful dialogue on the importance of housing to the state, its residents, and its economy — the better for California’s communities.

The California Chamber of Commerce Economic Advisory Council, made up of leading economists from the private and public sectors, presents a report each quarter to the CalChamber Board of Directors. The U.S. outlook for this report was prepared by council chair Christopher Thornberg, Ph.D., founding partner of Beacon Economics, LLC. The California outlook was prepared by Robert Kleinhenz, director of economic research at Beacon Economics.

The California Chamber of Commerce Economic Advisory Council, made up of leading economists from the private and public sectors, presents a report each quarter to the CalChamber Board of Directors. The U.S. outlook for this report was prepared by council chair Christopher Thornberg, Ph.D., founding partner of Beacon Economics, LLC. The California outlook was prepared by Robert Kleinhenz, director of economic research at Beacon Economics.