U.S. economic output has slowed to a crawl over the last three quarters—averaging less than a 1% pace of growth compared to 3% in the previous six quarters. Despite these disappointing results, prognosticators of the economy have, for the most part, not reduced their growth outlook for the nation by much. Most are still looking for rates in the 2% to 2.5% range.

U.S. economic output has slowed to a crawl over the last three quarters—averaging less than a 1% pace of growth compared to 3% in the previous six quarters. Despite these disappointing results, prognosticators of the economy have, for the most part, not reduced their growth outlook for the nation by much. Most are still looking for rates in the 2% to 2.5% range.

The reason for the relative optimism is that the headwinds which have slowed the U.S. economy in recent months have come largely from external sources—the global commodity glut, the slowing of the Chinese economy, political turmoil in the Middle East and Europe, and wild gyrations in equity markets driven by fears over all these issues. These problems have stalled U.S. exports and industrial production, and led to a decline in business investment—in particular a big runoff of business inventories.

In contrast, domestic demand has remained quite strong. Consumer spending added almost 3% to growth in the second quarter, more than enough to offset declines in business investment. Consumers are also increasing their spending for the right reason—they are earning more.

The U.S. labor markets continue to expand, adding 275,000 jobs per month in June and July after a weak spring. The construction, health care, professional services, and hospitality sectors have all been growing at a faster-than-average rate.

Also helping is weak inflation driven by low commodity prices and low unemployment rates that have finally shifted the economic balance toward labor to some small degree. Median real wages for a full-time worker have grown 4% over the past two years, still modest but better than the previous eight years when real earnings didn’t grow at all.

Positive Indicators

More importantly, there are a number of indicators that suggest the business spending pullback is ending and that overall investment trends will begin to turn positive again soon. In April, the Institute for Supply Management Purchasing Managers Index for Manufacturing climbed above 50, and in June the Industrial Production Index also started rising again with the best pace of growth since late 2014. Inventory to sales ratios are currently the lowest they have been since 2003—suggesting that businesses will need to start stocking up soon.

The housing market has also shown stronger signs of life recently. Sales of new and existing homes, while still far below long-run sustainable levels, have hit post-Great Recession highs in recent months. While tight credit remains a major impediment to full recovery, the improved financial situation of the average American household combined with ongoing low interest rates will lead to a faster pace of construction in the second half of the year.

Poor Global Outlook

As positive as all these signs are, the United States is unlikely to return to an average pace of growth within the next year or more. While the nation has muscled though the turbulence so far, the global outlook remains poor. The Chinese economy is still weak despite various policy measures put into place over the last year. Europe is growing again, but is dealing with issues surrounding deflation and the Brexit. And the commodity glut—while good for American consumers—continues to hurt growth prospects for many developing economies. As such, the overall outlook for U.S. growth remains much as it did last year at this time.

The only major change in expectations is in regard to interest rates and Federal Reserve policy. Given the recent weak U.S. growth data and the decline in interest rates driven by nervous investors seeking safety in U.S. markets following the Brexit, there is a mounting realization that low interest rates are going to be with us for some time.

California Outlook

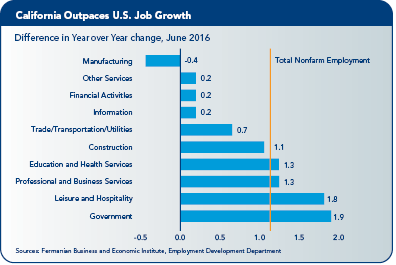

The California economy, like the nation overall, slowed its pace of growth over the past year. Still, the state remains one of the fastest growing economies in the nation.

Payroll employment growth has been above 2.5% over the last year—almost a full percentage point higher than the national average. California’s unemployment rate in July was 5.4%, still above the national average but by the smallest margin since before the Great Recession began.

Output growth also has been higher than the national average. According to data from the U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis, California’s gross state product (GSP) grew 3.1% from the first quarter of 2015 to the first quarter of 2016, compared to 2.1% in the nation overall. This is the fourth straight year that California has outgrown the United States as a whole.

Moreover, the gains in the state are not being driven by one industry or by one region. The tech sector is hot, but so too are the tourism, logistics, entertainment, and more traditional professional services sectors. Better incomes are driving demand for local services—and the health care, retail and construction sectors have all seen large jumps. The expansion is also largely statewide, with many regions seeing high rates of job growth.

California’s share of national employment recently returned to 12%, tied for the best ever with a record set back in 1990 before the onset of the early 1990s downturn. The state’s share of personal income is also currently at a record high level. Overall, California has clearly been an economic success story in otherwise difficult times.

Hurdles

This isn’t to say that the state’s complex regulatory system and high tax rates haven’t been issues—California would likely be doing even better in the absence of those hurdles. But the state’s other advantages in location, industry, and climate have, so far, persevered.

Taking a closer look at the numbers indicates that, much like the United States overall, the slowing of job growth in California is related to trade and investment. The state lost manufacturing jobs over the last year—after the previous year saw solid growth in these positions. Logistics, information and construction employment also slowed sharply. Recent data on industrial production, and the rebound in equity prices, suggest the second half of the year will look much better.

Regional Impacts

Regionally, the slowing of business investment and the cooling of the tech sector has affected San Francisco and San Jose. Still, both locations hold some of the top spots for overall job growth with year-over-year growth rates of 3% and higher.

Other rapidly growing economies were mainly in the central portions of the state—including Stockton, Fresno, and the Inland Empire. Bakersfield and Ventura both saw increases in the pace of employment growth after a weak previous year.

Housing Situation

Housing Situation

As good as the employment and income numbers have been (until recently), the CalChamber Economic Advisory Council almost universally agrees that the state will likely lose some of its steam in the next two years.

The high pace of job growth has been fed mainly by a supply of excess labor—in other words, the high unemployment rate in the state. Job growth has outpaced labor force growth by a factor of two over the last four years. With labor markets reaching full employment, high job growth rates can be sustained only by bringing workers into the state from other places.

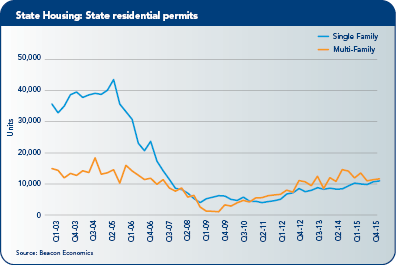

Unfortunately, California is unlikely to attract such workers given the rapidly growing cost of housing. Median home prices in the state recently crossed the $400,000 mark while in the red hot Bay Area, median prices can reach well over $1 million (in San Francisco). Inventories are very tight, with most major economies having between two and three months’ supply of homes on the market—on par with the peak of the housing market bubble.

But this is not like the last cycle because high demand has not been met with new supply. Single-family building permits are roughly one-quarter of what they were a decade ago.

The only bright part of new housing supply— multifamily units—is also below that pace. And the pushback against even modest development, particularly in the dense coastal regions, is heating up.

The problem is being widely discussed, but there is little consensus among political leaders as to how to deal with the mounting problem.

Staff Contact: Dave Kilby

The California Chamber of Commerce Economic Advisory Council, made up of leading economists from the private and public sectors, presents a report each quarter to the CalChamber Board of Directors. This report was prepared by council chair Christopher Thornberg, Ph.D., founding partner of Beacon Economics, LLC.

The California Chamber of Commerce Economic Advisory Council, made up of leading economists from the private and public sectors, presents a report each quarter to the CalChamber Board of Directors. This report was prepared by council chair Christopher Thornberg, Ph.D., founding partner of Beacon Economics, LLC.