The 2018 midterm election is finally behind us, and proved to be just as dramatic as would befit today’s hyper-charged political environment. Moreover, the final results pretty much assure that the drama coming out of Washington, D.C. will not lessen over the next two years of the Trump administration.

Indeed, without even taking a breath, it feels as if we are already in the run up to 2020. Will the Democratic takeover continue? Will the Republicans be able to hold the Senate and/or the Presidency?

While President Trump’s actions in the months ahead will be a major determinant of what happens in 2020, the outcomes will depend even more on where the economy heads over the next two years.

Beacon Economics’ outlook for the U.S. economy hasn’t changed much over the course of 2018, despite the fact that we are on the edge of the longest economic expansion in the nation’s history. Growth has progressed at a steady, sustainable pace since the 2015 commodity bust and mild economic slowdown that occurred that year.

Growth in the last quarter of this year is expected to come in at slightly less than 3%, with growth for the entire year reaching 3.2%. This modest jump is being driven by the fiscal stimulus plan passed by Congress at the end of 2017.

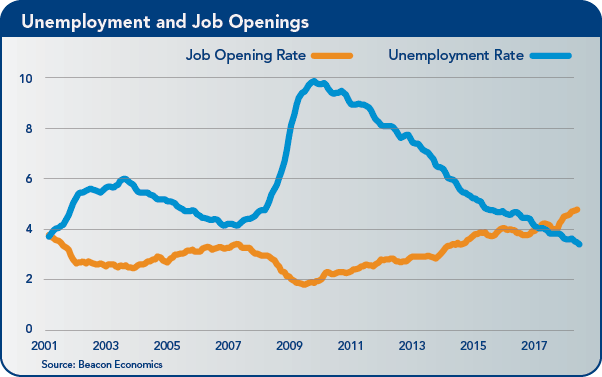

Outside of the rapidly growing federal budget deficit, the U.S. economy looks to be well-balanced in terms of the structure of growth with solid fundamentals including private sector debt levels, consumer savings rates, rising wages, the overall pace of homebuilding, and business investment. Unemployment is low—but job growth remains steady.

In short, Beacon Economics’ forecast remains boringly positive, and yes, that outlook is expected to stay in place though 2020. This isn’t optimism. Rather, we don’t have any real reason to think otherwise.

U.S. Trade Policy

The only major short-term worry has been wrapped around the direction of U.S. trade policy, but the worst scenarios have not materialized. Rather than unilaterally pull out of the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) as threatened, the United States instead negotiated a new trade agreement with our two neighbors and largest trading partners that, thankfully, looks almost exactly like the old trade agreement.

A brewing trade fight with the European Union that began with steel tariffs also has settled down, and there are now discussions about renewing talks and working toward a new trade agreement. It sounds a lot like T-TIP (Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership)—the EU-U.S. trade negotiations canceled by President Trump in one of his first acts in office—although this one will likely be better.

Yes, the China trade dispute is still brewing. But even a major trade war with China would not be sufficient to end the current economic expansion. The United States exports fairly little to China—only 8% of all the nation’s exports. And what does get shipped out typically doesn’t have a long supply chain.

The greater threat comes from the fact that the United States sources 20% of its manufactured imports from China. But the tariff-increased costs to U.S. importers have been largely offset by a 13% depreciation in the yuan relative to the U.S. dollar. And even as this article is being penned, there are reports, albeit few specifics, of a possible breakthrough in negotiations.

Data vs. Discourse

All said, from a technical or data standpoint there is not much change in Beacon Economics’ forecast for the U.S. economy. The framing of the outlook is another story.

While little has changed in the actual economy, much of the public discourse surrounding the economy has taken a sharp turn for the worse. This new wave of pessimism has likely been driven by the sell-off in the stock market, slowing home sales, and rising interest rates. Yet, as we see it, these short-run trends do not amount to anything that could truly threaten the current expansion.

Consider rising interest rates. Mortgages are now hovering just below 5%, up one percentage point from where they were two years ago. But while this is a recent high, it is hardly an historic one. In fact, it is still lower than at any time between 1968 and 2008.

Rates are higher, but they certainly aren’t high. And it isn’t surprising that rates have drifted up given that the economy has been growing well and there has been a sharp increase in federal borrowing.

Inflation Worries

One wrongly assumed reason for rising rates is inflation. After years of inflation tracking below the Fed-targeted pace, price growth finally increased above the 2% mark. This should have made investors more confident as deflation is less of a risk. Instead, it created a panic about the potential for further increases. Investors need not have worried: the most recent numbers now show inflation back below the 2% range.

Beacon Economics expects inflation to remain weak over the next few years. Oil prices are once again down based on high levels of U.S. output. Money supply growth also is very constrained at the moment. And yes, unemployment sits at an extremely low 3.7%—but if this were going to have an effect, we would already feel inflationary pressures on the economy.

Add it up and we don’t see much chance for rates to continue their upward drift. Moreover, the Federal Reserve seems to be taking the hint from the flattening yield curve and has been signaling a gentler future path on short-run rates.

Housing

The U.S. housing market has slowed as a result of the bump in mortgage rates, which has created considerable consternation. However, there is a big difference between a housing pause and a housing bust. The U.S. housing market is not overpriced, nor has there been much risky lending—or lending in general—occurring.

The pace of building has been reasonable, so there is no excess supply to worry about. That the market is responding to changes in interest rates is a good thing. Prices need to adjust to a higher carrying cost; once that happens, the market should get back on track. The slowing pace of sales is part of that process.

As for the stock market sell-off, it’s quite amazing that the recent dip has created such a wave of concern as it is no less than the sixth major sell-off since the Great Recession ended. And this says more about the stock market than the economy.

Excessive growth in equity prices followed by excessive sell-offs is the new normal in today’s high-speed electronic trading environment. There has also been a lot of good news for corporate America recently. Corporate taxes were cut sharply a year ago and gross profits are growing again after being flat last year.

So, for now, Beacon Economics is forecasting the expansion to continue and, barring some unexpected external impact, does not anticipate any major change in economic growth leading up to the 2020 election… for better or worse.

California Outlook: Growth Prospects for 2019

As 2018 progressed, it became evident that the California economy would continue to prosper despite the challenge of a tight labor market and concerns about the state’s housing situation.

Indeed, California’s economic performance was remarkably steady in 2018, fueled by expansion in the state’s industries, increases in incomes and wages, and in response to federal tax cuts enacted early in the year. Beacon Economics expects a continuation of these trends in 2019 and possibly into 2020.

As of October, the state is on track to add approximately 337,000 jobs in 2018, slightly less than the 340,000 added in all of 2017. Between February and October 2018, California has consistently added jobs at an average yearly rate of 2.0%, virtually identical to the same period one year ago.

The state’s unemployment rate has been in historically low territory for most of the year, dropping to 4.1% in the last two months, marginally higher than the U.S. rate of 3.7%. All in all, the headline numbers look good as we move from 2018 into 2019.

Job Gains

For the month of October, California’s 308,700 year-to-year job gain was the second largest among the 50 states. One-fifth of the increase occurred in Health Care (63,100), followed by Professional, Scientific and Technical Services, Leisure and Hospitality, Administrative Services, Government and Construction, and Transportation.

These seven industries accounted for 96% of the jobs added in October, and have consistently contributed the lion’s share of job gains throughout the year. Over the same period, three industries saw losses totaling 8,000 jobs, small relative to the total, but evidence of recent weakness in job growth in these areas.

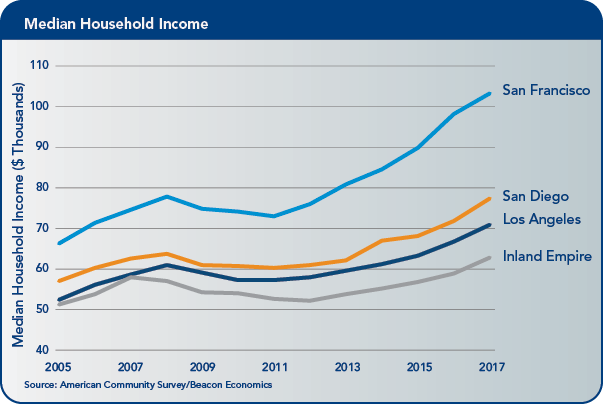

With California industries expanding in a tightening labor market, workers have experienced wage growth for several quarters running. In the second quarter of 2018, the average weekly wage for private sector workers was $1,265, up 4.6% over the prior year. Over the same period, prices in California increased 2.6%, implying a 2% inflation-adjusted gain in the average wage. This continues a recent trend of wage increases generally outpacing inflation, giving workers more purchasing power to drive spending and economic activity.

Most headline economic numbers for the state show that California maintained an edge over the nation throughout the year. Its 1.8% yearly growth rate in jobs surpassed the 1.6% gain for the United States in October. California’s gross state product growth outpaced U.S. gross domestic product (GDP) in the second quarter, with a 3.3% year-to-year gain compared to 2.9% nationally.

Over the same period, the average weekly wage in California increased more rapidly at 4.6% compared to 3.4% for the nation. However, the U.S. labor force grew by 1.0% over the first 10 months of this year, well ahead of California’s 0.4% growth rate.

The scant increase in the state’s workforce is cause for concern in 2019, although there is evidence that metro area labor force dynamics are such that rapidly growing regions continue to attract workers, most notably in the San Francisco Bay Area and the Inland Empire.

Growth Industries

Looking ahead to 2019, the question is, where will growth occur in California? The answer depends on the type of growth. Over the last three years, half of the job gains among the state’s industries have occurred in its population-serving sectors. This trend was led by Health Care, which accounted for 22% of California’s job gains over the three-year period from 2015 through 2018, followed by Leisure and Hospitality, and Government, and will continue through 2019.

Smaller but noteworthy contributions also came from the state’s leading external-facing industries, such as Professional Scientific and Technical Services (9%) and Transportation Services (9%).

The picture is considerably different when looking at the composition of growth in terms of output. More than 40% of the output generated during this three-year period emanated from just one industry, Information, with the gains mainly attributed to the tech-related segments of the sector.

Combine this with the 11% contribution from Professional, Scientific and Technical Services, and about half of all output generated in California came from tech-related activities over the last three years. Other external industries that weighed in with sizable contributions included Manufacturing at 7% and Transportation at 5%. Among those industries that contributed the largest job gains, only Health Care made a sizable contribution to output at 9% of the total.

Increasing Economic Pie

These findings provide insight into the future direction of the state economy. California can count on increases in employment among its population-serving industries in the coming quarters, but if the state wants to increase the size of the economic pie, it must look to its external industries to fuel that growth. That is the challenge that lies ahead for California’s newly elected governor and the rest of the state.

The California Chamber of Commerce Economic Advisory Council, made up of leading economists from the private and public sectors, presents a report each quarter to the CalChamber Board of Directors. This report was prepared by council chair Christopher Thornberg, Ph.D., founding partner of Beacon Economics, LLC.

The California Chamber of Commerce Economic Advisory Council, made up of leading economists from the private and public sectors, presents a report each quarter to the CalChamber Board of Directors. This report was prepared by council chair Christopher Thornberg, Ph.D., founding partner of Beacon Economics, LLC.