In the debate on health care, the two words most confused or misunderstood are “universal” and “single-payer.” They often are used interchangeably, and even standing alone, are defined incorrectly. This confusion or error has completely skewed the dialogue on what is an ideal model for California health care and how to improve health care in California.

Most people don’t realize that California is very close to achieving health care coverage for just about all Californians. Out of almost 40 million people, only 2.7 million don’t have coverage—approximately 900,000 of the uncovered are citizens or legal residents and the remainder are residents without proper documentation—so 97.6% are covered.

Even undocumented residents have access to health care in emergency rooms.

There are many ways of achieving universal health care. Most countries that have been able to achieve universal health care have not done so using a single-payer model.

A true single-payer health care system prohibits private health insurance. Health care in such a system can be delivered through either public and/or private hospitals and health care providers, but the payment for the health care must be made by a single entity, usually the government. A single-payer model eliminates cost sharing of any kind by the consumer, thereby increasing demand for a “free” service, requiring rationing of care.

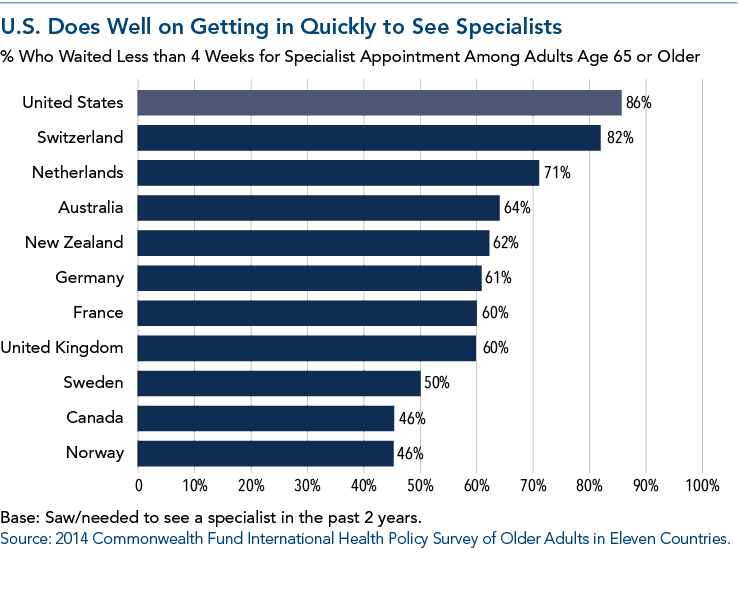

Wait times for routine surgeries in the United States that could be performed within a week or a month of an injury, have a four- to 12-month waiting period in the single-payer countries.

California and the United States are fortunate not to have a single-payer model, which is why there is not a prevalence of care rationing or unreasonable wait times for patients to be seen by providers or specialists, or for surgery.

In fact, in a comparison of 11 countries (see chart), the United States comes in first for the shortest wait times to be seen by a specialist (while Canada, a single-payer health care system, comes in second to last).

Unequal Comparisons

When compared to other countries, the United States spends more on health care than any other nation and yet ranks low in health outcome. The problem with the comparison, however, is that it is not equal and fair, and is based on data provided by the countries, which have different measurement standards or function under different medical standards.

Due to the frustration with the rising cost of health care, the recent narrative that has arisen and taken hold in California and the United States is that a single-payer health care system is the solution. The recent attacks on the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA) at the federal level, including the proposed elimination of the individual mandate and cost-sharing reduction subsidies, have only further fueled the argument that single-payer health care should be implemented.

Whether it’s at the national level or at the state level, single-payer advocates support their argument by comparing the U.S. and California health care systems to those of other countries. Such comparisons are problematic because the nature of health care systems in other countries that are idealized often is misunderstood.

For example, proponents of single-payer in California want to achieve universal health care in California, but define universal health care as health care for every resident of the state regardless of immigration status. Yet the countries single-payer proponents point to as having universal health care (which in fact by the widely accepted definition of universal health care do have it) do not provide health care to undocumented immigrants.

Similarly, proponents of single-payer health care point to many countries to emulate as examples of single-payer, yet the majority of those countries do not have a single-payer health care system, but rather a multi-payer system, which is what California and the United States have.

Reality Check

A closer look at health care systems around the world that are touted to be single-payer systems or ones that have achieved universal health care will lead to the conclusion that a single-payer health care system in other countries is very rare, does not result in more accessible health care, and is definitely not sustainable. A closer look also will reveal that countries which have achieved universal health care for all citizens and legal residents exempt many types of coverage and services that Californians believe to be essential health care and for which they expect health plan coverage, such as prescription medication, ambulance transport, and physical, occupational and speech therapy, as well as other services.

If implementation of single-payer health care 55 years ago in the nation’s northern neighbor is any lesson to California, it’s that California shouldn’t emulate a system that is slowly being abandoned. Canada’s own Supreme Court has stated that Canada’s health care system has violated patients’ “liberty, safety and security.”

California

California has the largest minority population in the United States. It has a nonwhite majority, with Hispanics representing 38.8% of the population and whites 38%. California also has the highest number of Asians and Hispanics of any state in the country.

Of the 39.25 million people living in California, approximately 6.8%, or 2.7 million people, are uninsured, and of this 2.7 million, approximately two-thirds are undocumented immigrants. This means of the 37.45 million citizens and legal residents in California, only 2.4% are uninsured.

To achieve universal health care in California, the question to answer first is, how do we define “universal”? The word “universal,” as defined by the seven countries analyzed in this article (Canada, Cuba, England, Australia, Taiwan, South Korea and Switzerland), is health care access or coverage for all the nation’s citizens and legal residents.

If that is the definition, California is very close to achieving universal health care at 97.6 % coverage. Of the 2.7 million people without coverage in California, approximately 900,000 are citizens or legal residents.

Although it doesn’t appear that the federal government will pay a share of covering health care for undocumented California residents, if the state wants to pay for coverage, it can do so without blowing up the existing system. It can choose to subsidize care for the undocumented as a state-only program. The health care access for undocumented residents can be provided regardless of whether there is a government-run system or the multi-payer system California has today.

The CalChamber has been a strong proponent of comprehensive immigration reform that includes a pathway to legal status for undocumented residents.

CalChamber Position

Rather than upending the health care system that polls say many Californians are satisfied with (except for costs), any reform to the system should focus on those who cannot gain access to affordable health care.

The CalChamber supports the following, including:

• Access to affordable health care through an insurance model or clinic model;

• Cost-containment on medication and treatment;

• Reducing administrative work for providers, such as by using uniform forms to claim reimbursement; and

• Expanding the investment by the state to increase the number of health care providers, especially physicians.

Condensed from the highlighted issue article in the 2018 CalChamber Business Issues and Legislative Guide. To read the full article, including its brief analysis of key features of other countries’ health care systems, visit www.calchamber.com/businessissues.